a thousand and one nights in Saint-Quay-Portrieux

The Moorish villa

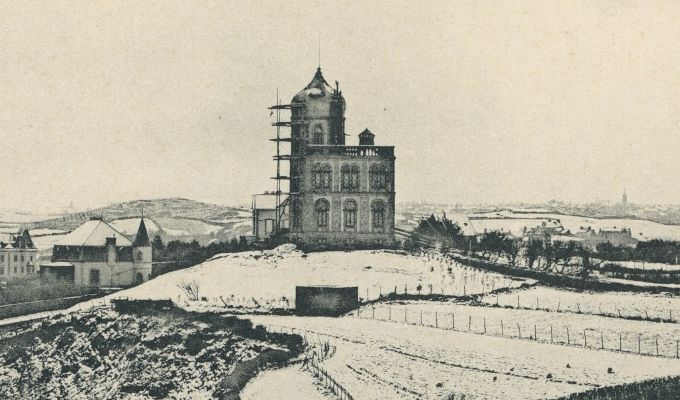

Turkish pavilion”, ‘Moorish villa’ – that’s how the inhabitants of Saint-Quay-Portrieux dubbed this surprising building, which appeared on the cliffs in the 1880s. It is also known as “Château de Calan”, after its builder, Count Victor Eugène de Lalande de Calan (1810-1899).

Born in Côtes du Nord (d’Armor), in Plélo, between Saint-Brieuc and Guingamp, and living in eastern France, not far from Nancy, Count de Calan led a military career. Retired from military service in 1872, he and his wife acquired several small plots of bare land over the next few years, to form the grounds of their future estate between sea and sky.

The reasons for the Calans’ architectural choices are unknown. A career soldier, his service record does not mention any foreign postings. But the Orientalist movement was very much in vogue at the end of the 19th century. Hadn’t it inspired and even fascinated painters and writers such as Eugène Delacroix and Pierre Loti, for example? The exact dates of construction remain unclear, and we don’t know the name of the builder.

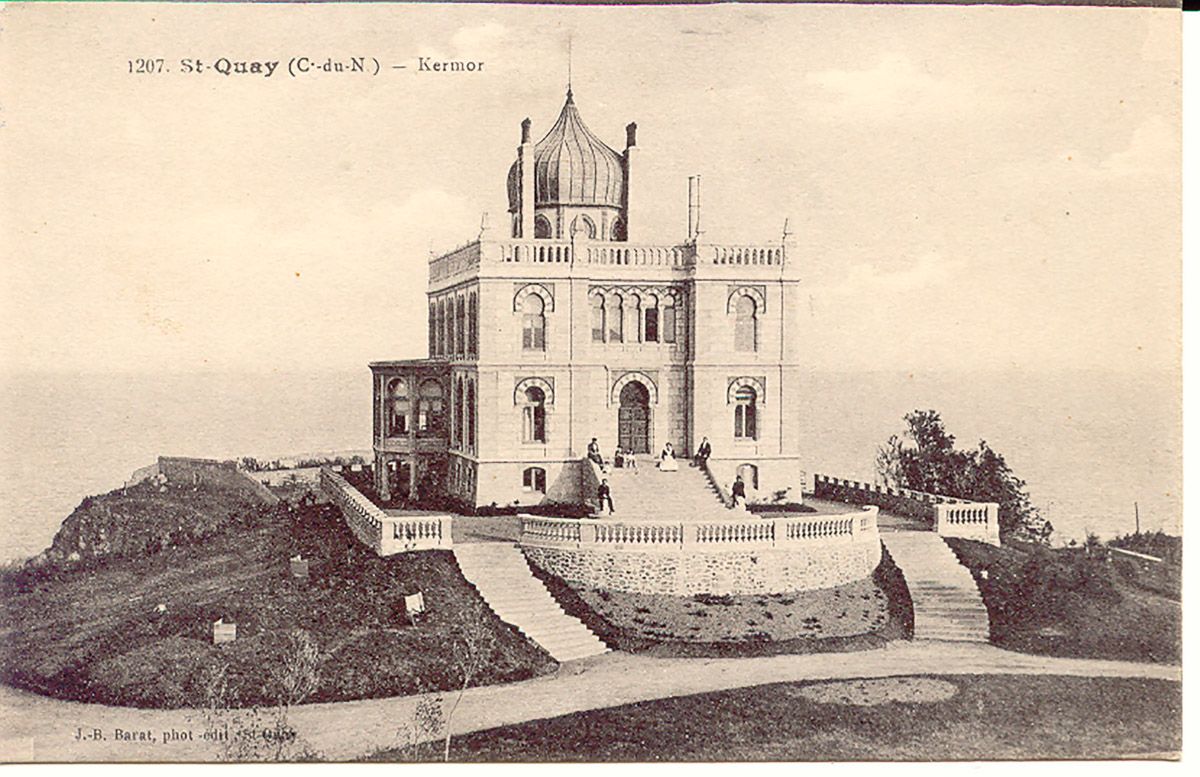

Around 1880, Villa Kermor stood proudly on the edge of the cliff. It was one of the first holiday homes in Saint-Quay-Portrieux. It’s a rectangular granite and schist building, with a basement level, a raised ground floor and a roof terrace dominated on the seaward side by a polygonal tower topped by a zinc bulb.

Architectural details such as pointed-arched windows with red brick surrounds, and a tower topped by a bulb (which served as a water reservoir), give it a resolutely oriental style and make it a striking structure in the Breton landscape. It is one of the jewels of the Quinocéen heritage. Inside, the panelling, coffered ceilings and door leaves are adorned with Moorish-style decorations on wood or plaster.

The family stayed there at a time when Saint-Quay-Portrieux was just emerging as a seaside resort and tourist destination. The train had arrived in Saint-Brieuc in 1863, but it took between 2 and 3 hours by stagecoach to reach Portrieux. The chemin de fer de l’ouest didn’t serve Portrieux and Saint-Quay until 1905. Until then, in summer, the village was frequented by a few families from the local bourgeoisie or aristocracy, and a few artists. Eugène Boudin (1824-1898) visited 11 times between 1868 and 1897 – as recounted by the “Eugène Boudin” sign on the port.

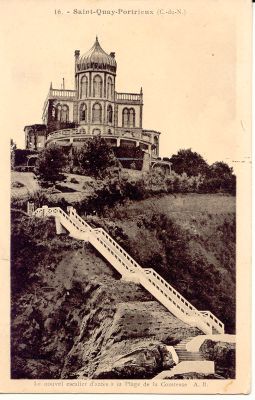

A few years after the death of the Comte de Calan, in 1909 his widow sold the property to her daughter and son-in-law, who considerably enlarged and embellished it.

The second life of the Villa Kermor

While continuing to acquire land to complete the park, the new owners carried out major renovations:

Retaining its “Moorish” appearance, the villa was enlarged, flanked by bow windows on the side façades, and surrounded by a vast terrace with balustrades, under which cisterns were installed to store water collected on the roof. This water was then pumped up into the turret’s bulbous cistern and redistributed inside (this system is no longer in use today!). In the 1920s, a large terrace was built on the sea side.

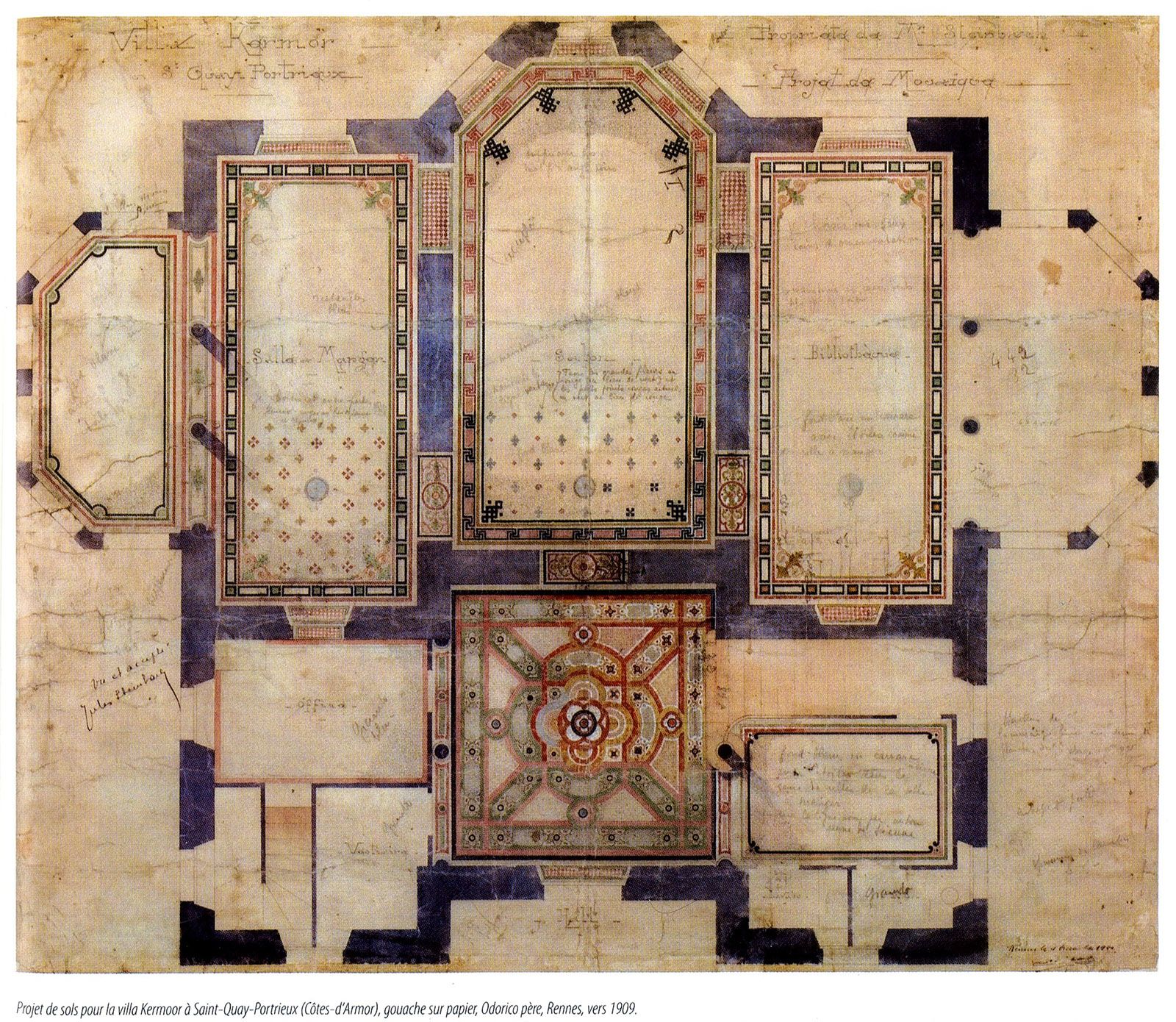

For the château’s interior decoration, they called on Isidore Odorico “father” (1842-1912), a famous mosaicist of Italian origin based in Rennes. He created a series of marble mosaics covering the entire ground floor and the corridors and bathrooms on the upper floors.

You can watch a video of the magnificent décor in the entrance hall: multiple interlocking quadrilobes of great chromatic richness (brown-red, yellow-ochre, blue-green, black, grey on a white background) which compensate for the lack of light in this hall.

It’s highly likely that the concrete base of the terraces and the mosaic floors were designed by Louis Harel de la Noé (1852-1931), a family friend, Ponts et Chaussée engineer and fellow student of Fulgence Bienvenue, father of the Paris metro. Louis Harel de la Noë designed and directed most of the engineering structures associated with the development of the railroads in the département.

The 80s and the listing as a Historic Monument

In 1955, descendants of the Calan family sold the property. The property passed through several hands without major alterations, until in 1980, in order to make the purchase more profitable, a new buyer added a hotel section, which he ran himself for a few years. The hotel part alone was then sold. Villa Kermor remains a private property, separate from the hotel section.

The mosaics, combined with the originality of the building, led to Villa Kermor being listed in its entirety as a Historic Monument in 2018.

It is one of the few remaining examples in Brittany of the Orientalist vogue, and the mosaic ensemble by Isidore Odorico senior is, as the report by the Regional Department of Cultural Affairs, which led to its listing in 2028, states, ‘one of the most accomplished, complete and well-preserved’.