THE CALVARY AND ITS RESTORATION

This calvary, listed as a Monument Historique on January 25, 1918, dates from the end of the 15th century or the very beginning of the 16th century, a period of affirmation of Breton art. It has no equivalent in the Côtes d’Armor.

As a sign of devotion, some noble families had their own calvary built. This is thought to be one of them.

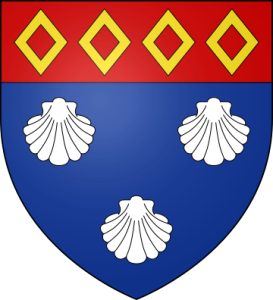

It bears the arms of the Nicol and Percevaux families, and stood on the grounds of the Rue Louais manor house. Towards the end of the 15th century, a plague epidemic decimated the population, apparently sparing the local lords.

It was perhaps to thank heaven for its clemency that they had this calvary erected in the heart of the hamlet, at the crossroads of the roads to Saint-Quay, Etables and Plourhan.

The calvary of rue Louais

Placed on a small mound, it was particularly revered by the villagers, who came here on pilgrimage in times of epidemic, recited novenas to ward off drought and rain, and invoked Saint Barbara during storms. As many of the village’s men went out fishing, Notre-Dame de Pitié was also prayed to in times of storms, when shipwrecks were feared.

During the years of the Terror that followed the Revolution of 1789, the inhabitants, fearing that their Calvary would be pulled down, dismantled it to preserve it and hid its various parts in neighbouring farms and houses.

It is said that in the base they found a hollowed-out stone containing parchments telling the story of the origin of the Calvary, as well as writs granting various indulgences to those who came to worship there… Unfortunately, these documents have never been found!

In 1862, at the request of the rector of Saint-Quay, the calvary was reassembled in its original place. Certain lost or broken parts had to be replaced or rebuilt as best they could, such as the shaft which, originally made of light-coloured granite, was replaced by a shaft made of darker granite.

Moving the calvary

In 1986, work began on the new deepwater port at Saint-Quay-Portrieux. It will be built between 1988 and 1990. In anticipation of the passage of the trucks transporting the stone blocks for the riprap, taken from nearby, the calvary was moved a few meters and set back on private land. It would be many years before the calvary returned to its rightful place!

A beautiful restoration in 2020

Somewhat “forgotten” on this site, the monument is deteriorating. In 2017, local residents and an association, l’Amicale des moulin, lavoirs et fontaines, alerted the Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles and the Architecte des Bâtiments de France to the urgent need for action.

With the original site on the municipal boundary, the communes of Binic-Etables sur Mer and Saint-Quay-Portrieux have agreed to carry out the restoration, under the supervision of a qualified architect, with the help of subsidies from the Département and the Région.

The dismantling of the calvary, its cleaning, the carving of missing elements, the rebuilding of the shaft in a light-colored granite of the appropriate tone, and the consolidation of weakened elements were all carried out by Breton companies who did a magnificent job. Sketches and drawings made in past centuries, mainly in the 19th century, helped restore it as closely as possible to its former appearance.

Henri Frotier de la Messelière – 1931 – Archives Départementales Côtes d’Armor

Then, the calvary was returned to the place it had occupied for centuries: in the center of the crossroads. It was inaugurated on September 18, 2020, with little fanfare, as restrictions linked to the COVID 19 pandemic had not been lifte

As originally, its base rests on a one-metre elevation, surrounded by a masonry wall of local stone. Two granite jambs mark the entrance to the enclosure, enclosed by a wrought-iron gate. Access is by three steps.

The original orientation has been respected: Christ’s birth is to the east, his death to the west.