The symbolism of calvaries

Breton Calvaries

Monumental calvaries, crosses erected and adorned with a crucifix and sculptures, are a distinctive Breton feature. They take their name from Golgotha or Calvary, the name of the hill on which Jesus was crucified according to the Christian Gospels.

Most of them were installed around the 15th and 16th centuries, a period of affirmation for Breton art, to make religion more present to the local population. They were also probably used to implore heaven’s mercy in times of epidemics or climatic disasters affecting harvests and causing famine. The plague, in particular, was rife in Brittany from the 14th to the 16th century, as were typhus, cholera and smallpox later on…

These calvaries had a messenger function. At a time when life expectancy was little more than 30 years, this vision of the Cross called for faith in the Resurrection.

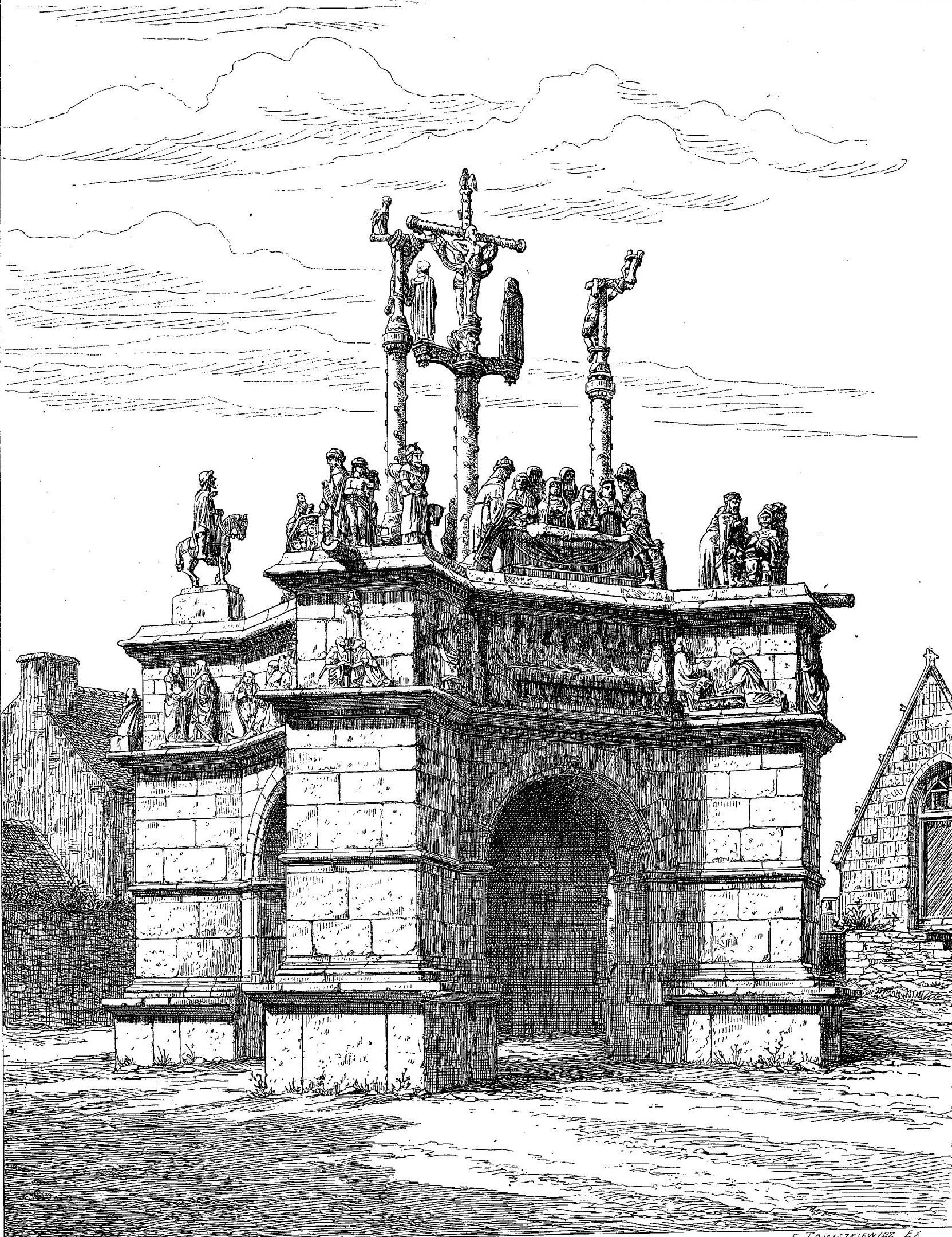

Whether simple, as here, or monumental, as at Lanrivain (22 – Côtes d’Armor) and in the parish enclosures of Guimiliau (29 – late 16th) or Pleyben (29 – late 16th), for example, they have the same structure: a massive, unadorned base is surmounted by one or more crosses adorned with figures representing episodes in the life of Christ. A calvary may feature a large number of figures and scenes.

Calvaire de Lanrivain

Calvaire de Guimiliau

Calvaire de Pleyben

Calvaire de la rue Louais

“Reading” the calvary on rue Louais

This calvary, erected at the end of the 15th century on the initiative of Lords Nicol and Percevaux of the neighboring Rue Louais manor house, was probably originally painted, as was customary in the 15th century.

It features 23 figures in several scenes at the top and base of the cross.

Displayed on both sides, the coat-of-arms of the donor families is present, albeit very faded.

The cubic base, symbolizing the material world, served as an offering table for celebrations. At its corners, four evangelists hold a phylactery, announcing the universality of salvation.

The octagonal calvary column was redesigned when the monument was restored in 2020. Some monuments had growths on their shafts suggesting buboes from the plague, a terrible epidemic that killed people from the 14th to 16th centuries. This may also have been the case here.

Calvaire de Lesneut (14e siècle) – Excroissances buboniques.

The upper scene, facing east on the sunrise side, depicts Christ the Light of Men, illustrating the spiritual maternity of the Virgin in majesty, offering up her son. Her crown is supported by an angel. At her feet, on the plinth, is St. Catherine of Alexandria (287-305, a great scholar who affirmed her faith even to the point of the wheel), depicted next to the wheel of her martyrdom. Catherine may well have been the patron saint of the Dame du Manoir in rue Louais.

On the other side, facing west, the crucifixion in the presence of Mary and John, where angels collect the spilt blood. Below, the Pietà confirms Mary’s faith in the experience of death.