Louis Malbert, the Iroise and deep-sea rescue

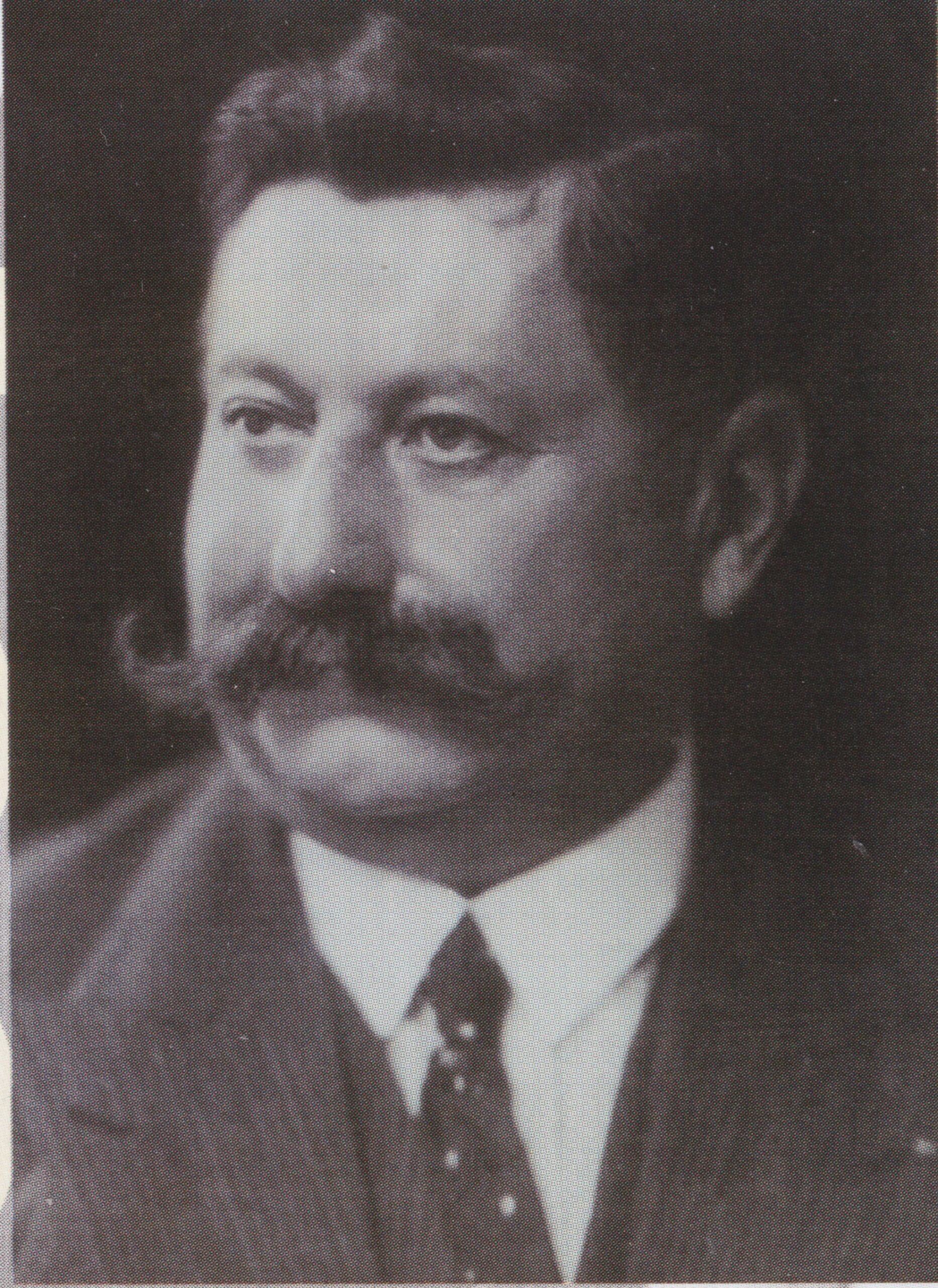

Louis Malbert

On August 21, 1950, a stele was erected at the foot of the Saint-Quay-Portrieux semaphore, thanks to the talent of Breton sculptor Armel Beaufils. On a single block of granite, two bronze bas-reliefs depict the profile of Commandant Malbert, and the silhouette of the Iroise, the deep-sea tugboat on which he saved many lives.

Louis Malbert was born on July 18, 1881 in Saint-Quay-Portrieux into a family of building contractors. Fatherless at the age of 10, he was raised by his mother, grandmother and aunt. He soon showed an interest in the sea, encouraged by his tutor Albert Gourio, a long-distance captain also from Saint-Quay-Portrieux. Louis Malbert began his career as a cabin boy on the three-masted KerJoseph at the age of 13.

Six years later, he attended officer cadet courses in Paimpol, where he was awarded a Master Mariner’s certificate. He sailed for seven years as an officer before obtaining his first command in 1907, at the age of 26, on the Pierre Loti, an 84.7-meter three-master. He went on to command other tall ships, rounding Cape Horn 17 times.

In February 1919, commanding the four-masted schooner Champigny, he was landed in San Francisco by the Spanish flu. Although barely saved, he was declared unfit for long-distance sailing.

Back in Saint-Quay-Portrieux, Louis Malbert’s second life began, five years of transition before his encounter with the Iroise.

Less than forty years old and unable to be satisfied with his early-retirement status, Louis Malbert left his hometown for Brest, where his uncle Gourio had just opened a ship-repair yard. Here, he took part in the refloating of several ships, including the cargo ship Saint-Nicolas, grounded at Bénodet, and the liner Lipari. At the same time, he continued to sail coastal and fishing vessels. When he boarded the Léon Bourdelles des Phares et Balises, he discovered the Iroise Sea and its many dangers.

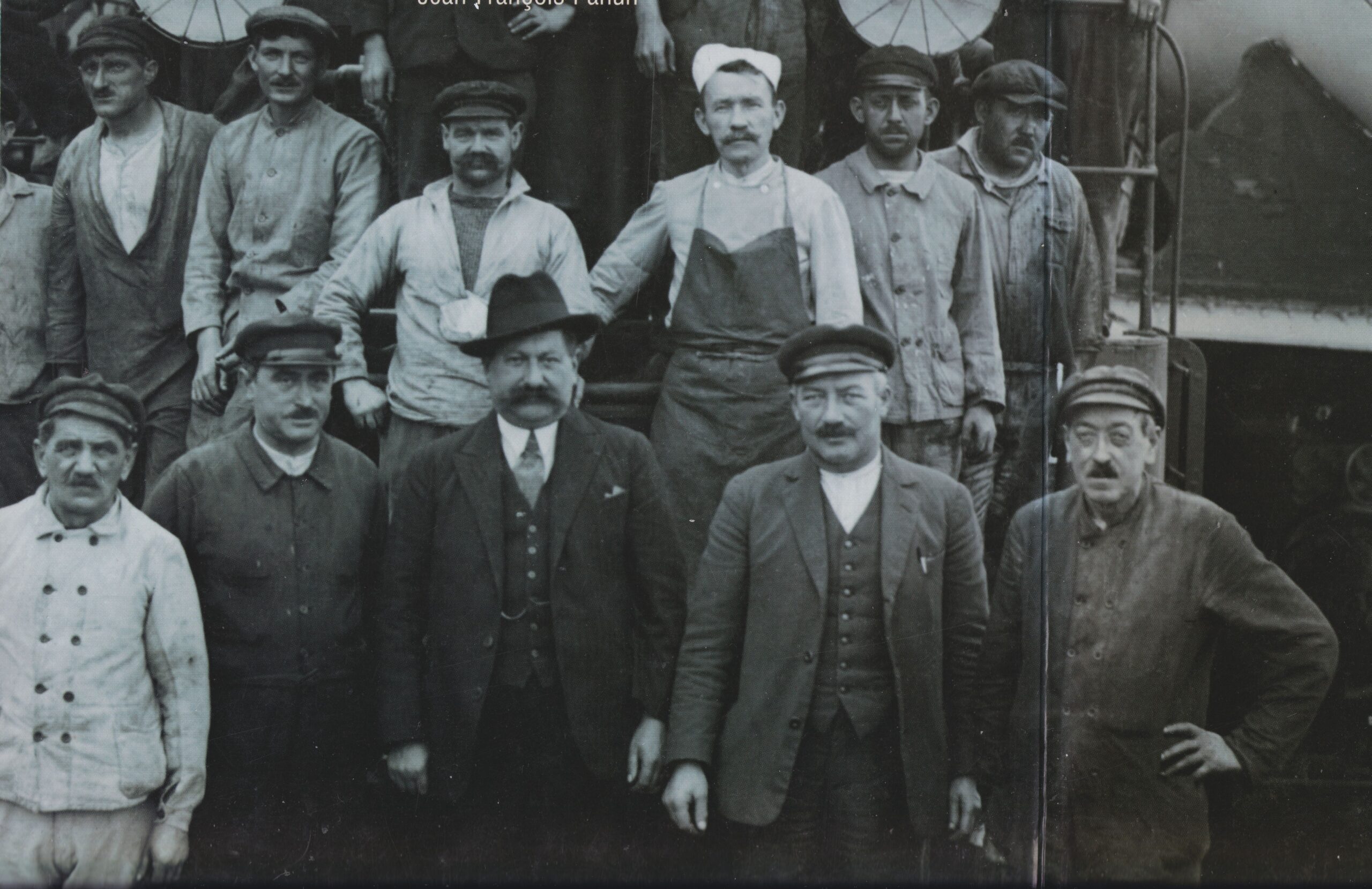

Louis Malbert et son équipage.

It was then that he was recruited by Union Française Maritime (a company founded in 1922 by Henri Cangardel) to bring a former Russian icebreaker converted into a tugboat from Saint-Nazaire to Brest.

For the first time, on December 6, 1924, Louis Malbert’s name appears on the crew list of the Iroise. Man and ship had finally met. Their shared adventure would come to an end at the end of September 1931, at the end of seven years devoted to towing on the high seas, during which the legend of a sailor and a ship linked by the same destiny would be forged.

During this short period, the Iroise made a total of 120 outings and took 63 tows that gave rise to compensation claims.

Towing on the high seas

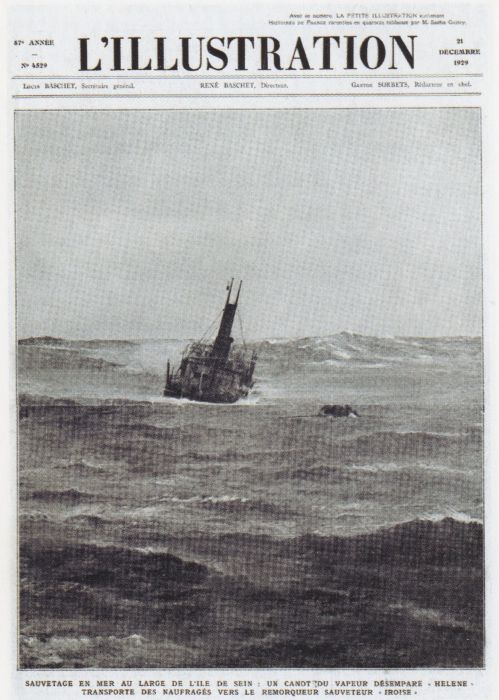

Remorquage de l’Aghia Marina le 29 décembre 1929.

The “high seas” refers to the maritime area more than 20 miles from the coast. Vessels in difficulty are generally large, and the sums involved are considerable, both for the shipowner and for the various tugboat companies.

Since the installation of the wireless, ships in distress have been able to report and request assistance, and the intervention of an ocean-going tugboat has become possible. However, while saving human lives at sea is the duty of every sailor, and can only be done free of charge, towing vessels in distress is not. In this field, several companies coexist and compete with each other.

Maintaining a fleet of tugs, ready to intervene at any time and in any weather, is necessarily expensive. The machines have to be kept under pressure, even when the ship is alongside the quayside, and a crew of at least twenty men has to be on constant alert, so as to be able to set sail as quickly as possible to arrive at the scene of the wreck before the competition. Since 1910, any intervention by a tugboat has required a contract to be drawn up between the tug and the owner of the vessel in difficulty.

However, remuneration of the tug is not automatic. It is stipulated that if the boat requesting assistance is not saved, or can do without the tug’s services, all costs incurred remain the responsibility of the tug. This is the famous “no cure, no pay” clause. At the time, it was not uncommon for the assisted vessel to discreetly cut the towline, once the danger had passed. The rescuer would then have worked for nothing.

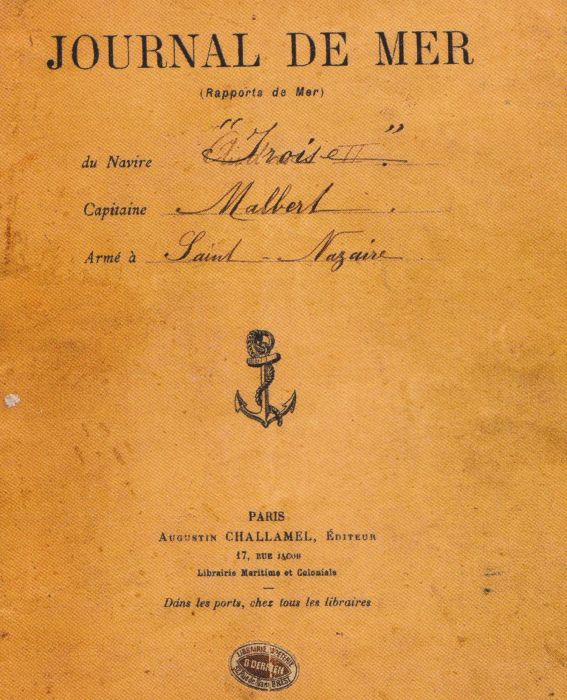

Journal de mer de l’Iroise, Capitaine Louis Malbert

Once ashore, the principle of a bond, the amount of which is fixed immediately, is negotiated between the shipowners. If after forty-two days no claim has been made against the bond, the deal is concluded and each party waives the right to third-party arbitration.

If this is not the case, the dispute is submitted to arbitration, and any remuneration is determined on the basis of the cost of towing, as well as the value of the cargo salvaged. The arbitrator’s decision is based on the sea reports drawn up by each of the captains “in a sincere and honest manner”.

In those years, the image of the salvor on the high seas was that of a true “bounty hunter”. One of Louis Malbert’s merits was to change this image, prioritizing the rescue of the men on board over that of the cargo. “3000 lives at the end of a cable”, as writer Roger Vercel once wrote. Indeed, many sailors would have perished had the Iroise not plunged its bow into the furious sea whose name it bears…

In 1933, the Iroise completed her final voyages before being sold. The ship was finally dismantled in 1951.

L’Iroise à quai.

At the age of 52, Louis Malbert was not idle for long. He moved to La Rochelle, where he ran a repair and salvage yard. He died there on January 28, 1949.

Today, the rules of towing have changed. Since the sinking of the Amoco-Cadix (1978) and its consequences for the environment, it has been decided to charter a permanent fleet of Remorqueurs d’Intervention d’Assistance et de Sauvetage (RIAS) distributed between three stations (Brest, Cherbourg and Toulon). The government drew on the experience of the Abeilles company and its powerful new tugs. This system enables the Maritime Prefect to call in a tug if he considers that a vessel represents a danger to its crew or to the preservation of the coastline, even against the wishes of its owner.

Since 2005, the Abeille Bourbon has been moored at Quai Malbert in Brest. Chartered by the French Navy, 365 days a year, she has to be ready to sail within 40 minutes, 24 hours a day. As soon as winds reach 50 kms/h, l’Abeille is put on weather alert and leaves its quay in Brest for Ushant. Protected in Stiff Bay, l’Abeille is ready to leap onto the Ouessant rail in the event of an emergency.

L’Abeille Bourbon dans le raz de Sein.

The page has now been turned: assistance to ships in difficulty is no longer a matter for adventurers.

What remains is the extraordinary story of an ocean-going tugboat and its unusual captain, as told in “Remorques”, a novel (1935) by writer Roger Vercel, and in Jean Grémillon’s film (1941) based on it.