the economics of deep-sea fishing

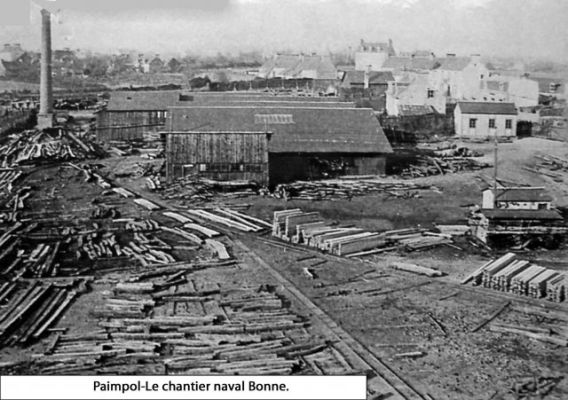

Chantier naval – Louis Marie Faudacq.

The livelihood of many families

For almost three centuries, cod fishing in the distant waters of Newfoundland or Iceland was an essential activity for Brittany, but also for France. It was disrupted by periods of war, which brought fishing to a standstill: a large number of sailors had to serve in the “Royale”, and cod ships were easy prey for privateers looking for a catch.

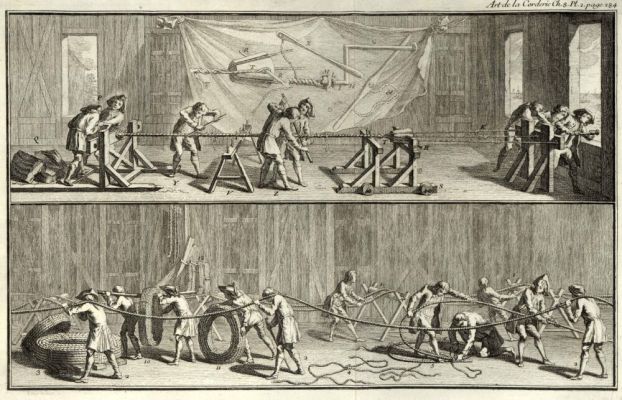

At the end of the 18th century, it was estimated that some 12,000 sailors left in this way every year from March to September. More than half the total number of fishermen in France. If we add all the related trades – shipbuilding and repair, sailmaking and rope-making, bunkering, fish processing and transport, etc. – this gives an idea of the vital importance of this sector for a French population of 25,000,000.

Cod accounted for some 60% of the tonnage and value of the entire French fishing industry.

In Brittany, fishing was one of the main sources of income for both coastal and inland populations. The Bay of Saint-Brieuc, with the ports of Le Légué, Dahouët, Binic and Portrieux, sent some of the largest contingents of men and ships to Terre Neuve and the banks: 2,600 men in 1822 and 4,000 in 1862. In 1843, Binic was France’s leading cod port, with 33 ships and some 1,600 sailors on board. From 1850 onwards, Icelandic fishing took over, until the beginning of the 20th century. It employed fewer sailors because crews were smaller, but the activity of the Paimpol shipyards and all that revolved around them was flourishing and supported an entire region.

The last great cod ports were Saint-Malo, Dunkirk, Fécamp and Bordeaux.

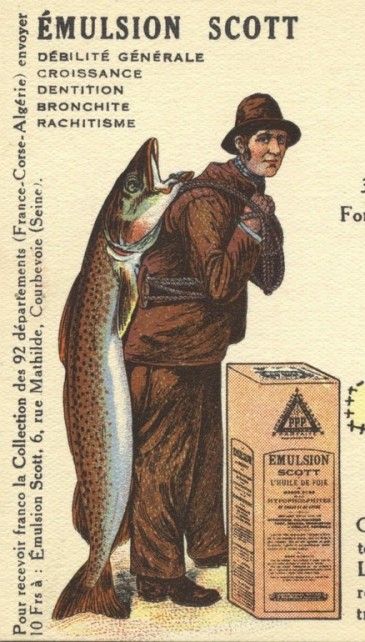

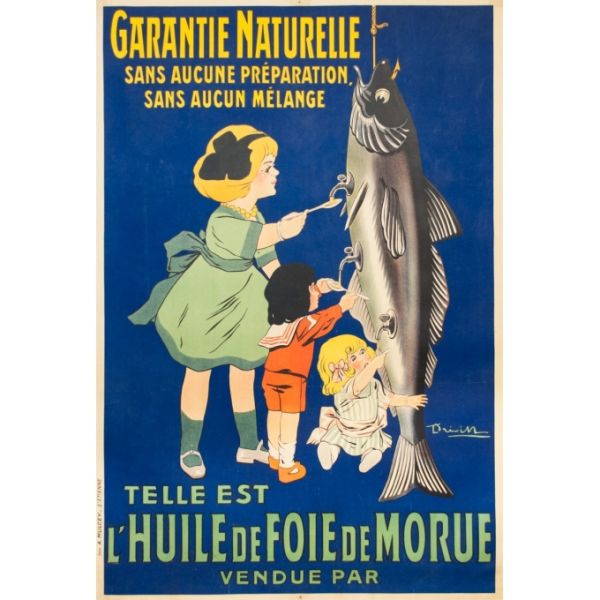

Necessary food

This fishery provided people with a nutritious, relatively inexpensive foodstuff that was easy to transport and preserve. At the end of the 18th century, there was an average of 170 lean (meat-free) days imposed by the Church. Cod, nicknamed “poor man’s beef”, provided an inexpensive way to balance a family’s diet. While fresh cod was a luxury product, salted or dried cod, along with herring, was the alternative, particularly during Lent.

Cod recipes were numerous: boiled, grilled, brandied, with tomato… it was eaten everywhere, in southern Europe, Brazil, the West Indies and many other countries.

It is estimated that 45% of this catch was exported, bringing in foreign currency. The finest cod were destined for the big cities and for export, and a large proportion of the catch was marketed directly in Marseille and other Mediterranean ports. Lower-quality cod was shipped to the West Indies to feed slaves and, after the abolition of slavery in 1848, plantation workers.

Le port de Marseille – Joseph Vernet – 1754

A reserve of sailors…

From the 17th to the 19th century, all governments considered deep-sea fishing to be the best training ground for sailors, and the least costly for the state. If need be, these seasoned fishermen with their knowledge of the sea would be available to train the crews of the Royal Navy.

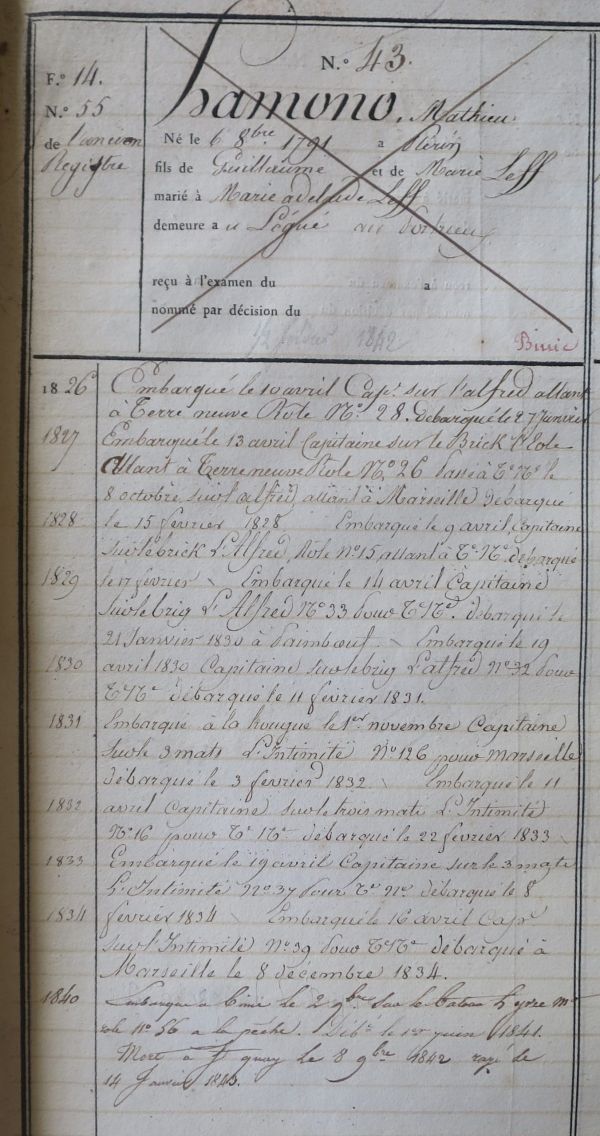

At a time when armed control of the seas was a key issue of sovereignty, since Louis XIV and Colbert the class system, unique to France, enabled the Royal Navy to find the men needed to build, maintain and maneuver the ships of its navy. All seafarers, including mousses, had to be registered with the administration to serve in shifts on warships, sometimes for several years at a time.

In exchange for this compulsory service, seafarers enjoyed a number of benefits: a small pension paid after years of navigation, a disability fund financed by a percentage deduction from all pay, and a small pension paid to widows. In a way, this was the forerunner of provident schemes.

Exemple de registre matricule 1826-1840 – Service Historique de la défense – Brest

A subsidized sector

Great fishing was therefore an essential activity. And, as such, it was generally supported.

Aware of its vital importance for coastal populations and the hinterland, its role in balancing trade, and the quality of the sailors trained in fishing, all regimes, from royalty under Louis XIV to the Third Republic, implemented various measures to support the sector, as was also the case in England. For example: tax breaks on the purchase of salt and on taxes levied on sales, bonuses for ships and sailors, bonuses per quintal of cod exported…

The aim was to guarantee a certain level of profitability for the shipyards and prevent their collapse, which would have plunged an entire population into poverty and deprived the royal (and later national) navy of trained sailors.

These measures will remain in force until the end of traditional fishing. By the end of the 19th century, the scarcity of cod banks, the closure of territorial waters, changes in fishing methods, rising standards of living and changing eating habits all led to a sharp drop in cod consumption. After the First World War, cod fishing died out completely in the Bay of Saint Brieuc.