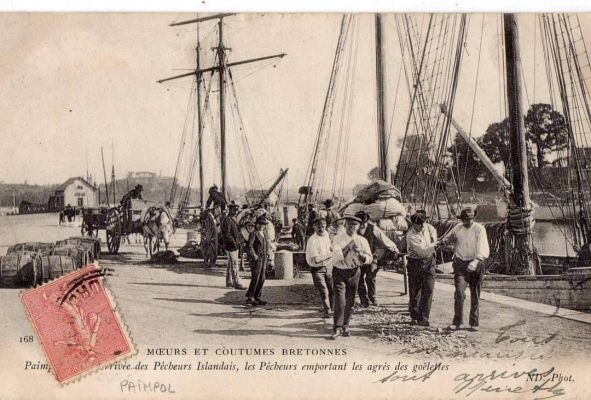

Departures and returns, equipment and crew, life on board

Binic bénédiction avant le départ

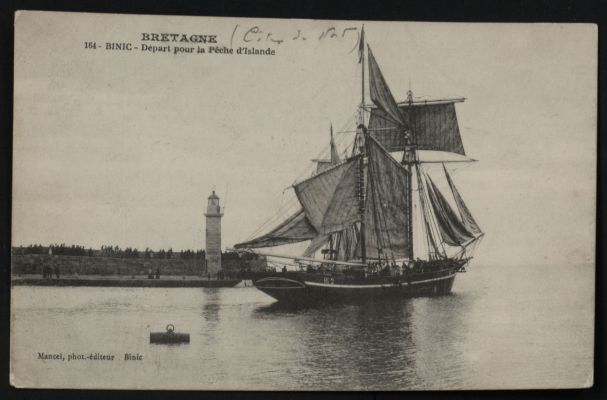

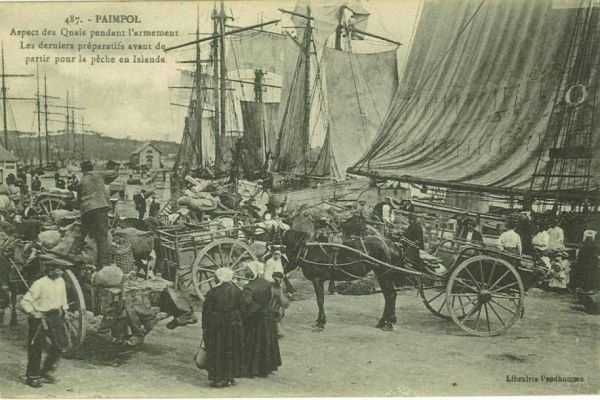

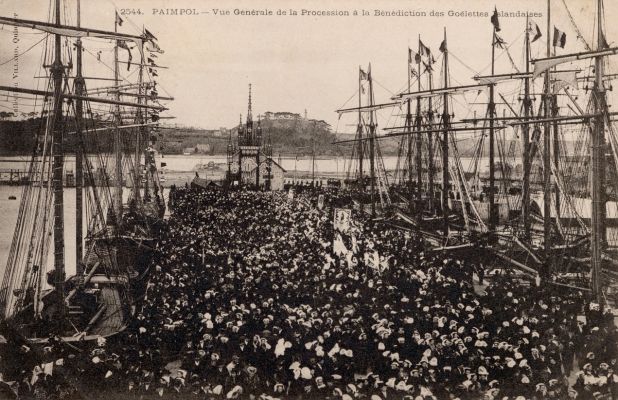

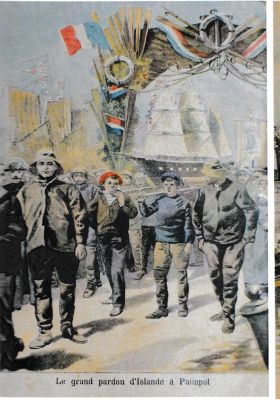

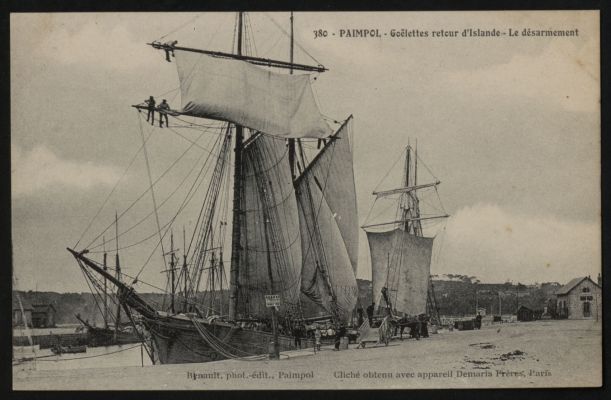

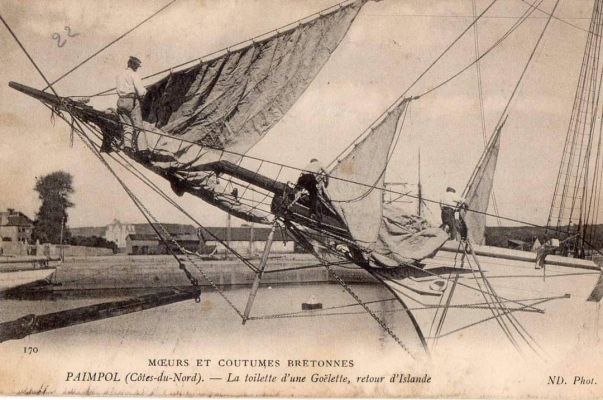

Departures and returns

With these dangerous campaigns lasting half the year, departures and returns were emotional moments.

Used to sailing together, the ships from the Bay of Saint-Brieuc gathered in the deep channel of the Portrieux harbor before departure.

La jetée du Portrieux – Emile Querangal – 1830 (détail)

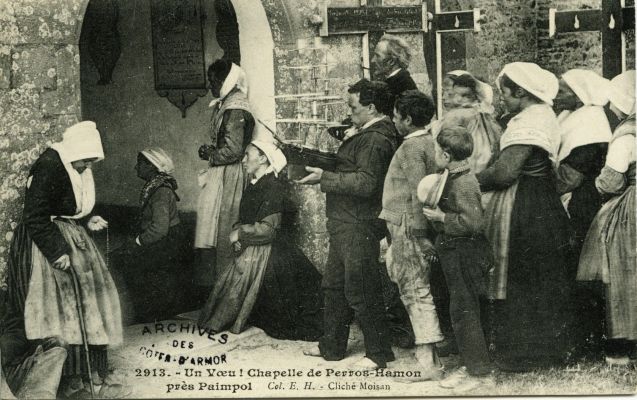

In the days leading up to it, everything was in a flurry of preparation and loading. Sailors liked to place themselves under the protection of the Virgin Mary. Those from Le Portrieux made their devotions at the Notre Dame de Kertugal chapel, built in 1828. Blessings for ships and crews, pardons – everything was done in the hope of a clement voyage. Listen to the hymn to Notre Dame de la Garde on the Notre Dame de Kertugal panel…

As they left, they saluted ND de la Ronce in front of the large beach (see Parish Church sign).

The return journey was a time of mourning when a ship or sailor went missing. But in every port, the inhabitants came to the quays and foreshores to welcome the ships, and the carts were ready for unloading, as in Boudin’s painting on the panel, it was a whirlwind of activity and jubilation. Then came the time to thank the Virgin Mary….

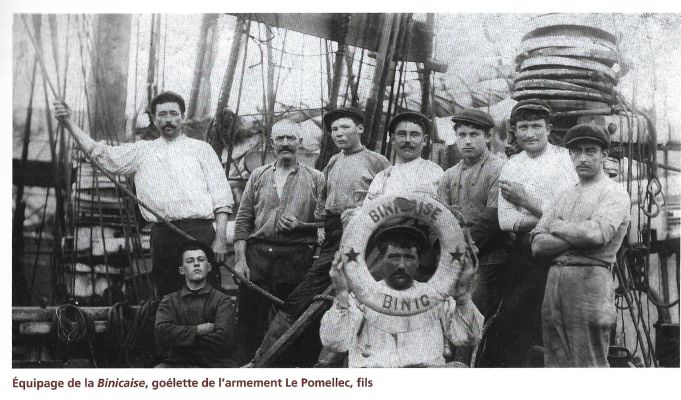

Shipowners and shipping lines

In the days of deep-sea fishing, the shipowner was, as nowadays, the person who owned the vessel, or the majority of the vessel’s shares. He was responsible for “fitting out” the vessel, i.e. maintaining it (hull, sails, rigging), bunkering it (providing equipment, supplies and everything needed for the campaign: salt, orins, hooks, food, water, wine, cider, gnole, tobacco…), recruiting and paying the crew and selling the cargo. He was also responsible for living conditions on board, safety and medical care, and for complying with all regulations.

In Portrieux, as in the other ports of the Bay of Saint-Brieuc, the shipowners were “small” shipowners. They owned a maximum of 4 or 5 vessels, in stark contrast to the shipping companies in Saint-Malo or Granville, which could own as many as 20.

Sometimes former captains, they were more often landowners and merchants. In the Bay of Saint-Brieuc, the families of shipowners and ocean-going captains merged: shipowners gave command of ships to their sons or sons-in-law, while captains at the end of their careers often acquired shares in ships.

The five main shipowning companies in Portrieux were active in this way for three or four generations, some of them managed by a widow, assisted by sons or sons-in-law who sailed.

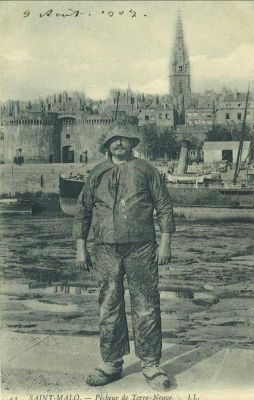

Crews

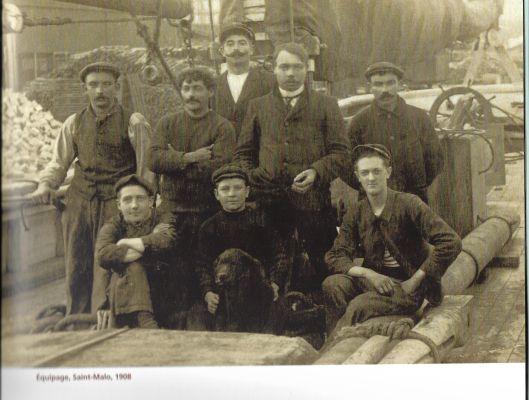

A deep-sea fishing vessel was commanded by a licensed captain, assisted by a mate. Responsible for running the ship and crew, his appointment was recorded in a notarial deed in which the shipowner specified his duties. He was often responsible for assembling the crew.

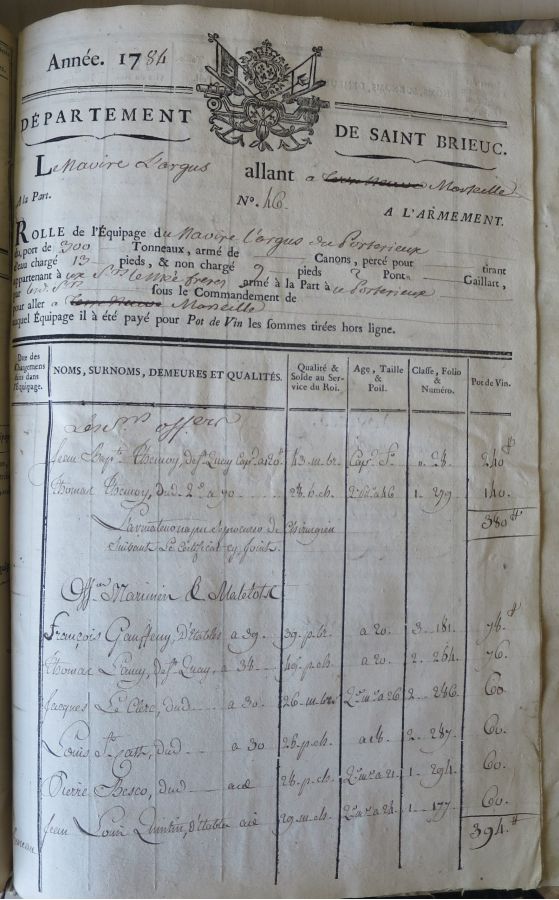

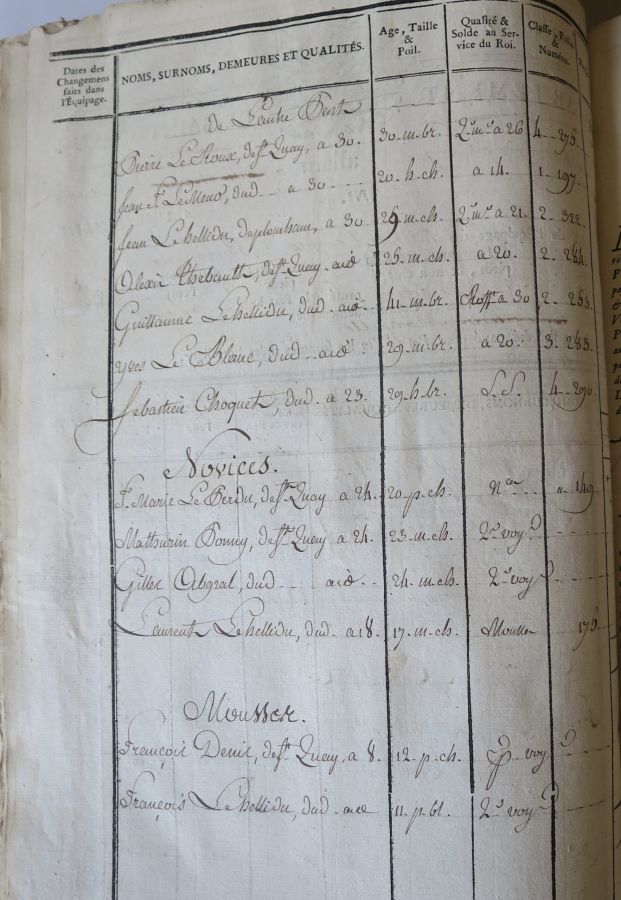

Each member of the crew had to be registered as a seaman, and signed a contract of engagement with the shipowner. The “rôle d’équipage” is a document listing all the crew members, their identities and functions, as well as the emoluments and advances paid before departure.

Rôle d’équipage de l’Argus du Portrieux – 1777 – Service Historique de la Défense – Brest.

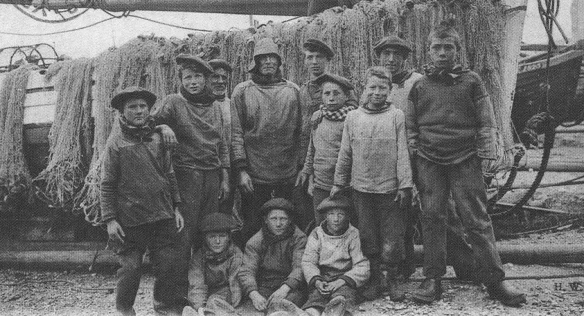

In addition to the captain and mate, a Newfoundland crew (40 to 60 men, depending on the size of the vessel) included a lieutenant, a fishing master, a salter, a cook, a number of fishermen, mousses (generally aged between 12 and 15) at a rate of one for every 10 men, and novices (aged between 16 and 25 but inexperienced), one for every four men.

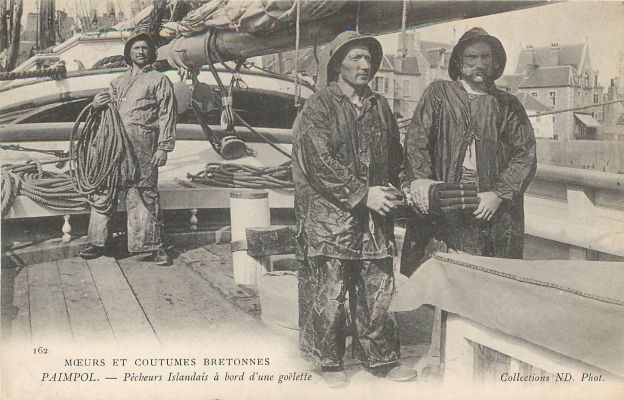

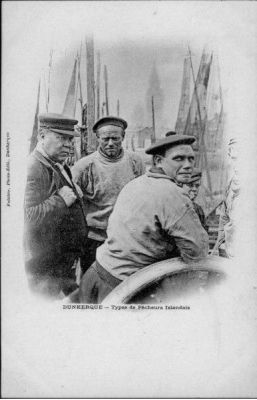

Some fishermen also fulfilled a special function: carpenter, sailmaker, capelanier (in charge of the “boëtte” or bait for the lines), and the specialties attached to fish processing: dresser, stripper, slicer… For the shoals, it was specified for the sailors whether they were “dory skippers” or “dory foremen”, the wages were not the same. For Iceland’s particularly harsh sea conditions, the smaller crew – often less than 30 men – had to be skilled in fishing from the shore, and could not include more than two men who had never been to Iceland. These sailors most often hailed from the coast between Paimpol and Erquy…

The role of the novices was to go where they were needed. The mousses were mainly responsible for cooking, cleaning and serving the captain and other sailors, and could also help dress the fish. They were frequently subjected to bullying and mistreatment that we can scarcely imagine… And yet, most of them continued to sail in the years that followed.

Life on board

No comfort, no hygiene

In Newfoundland, the sailors slept in makeshift dwellings, without comfort or hygiene, but on land where they had the opportunity to grow a few vegetables. The work was very hard, 18-hour days, and the climate harsh, as the island was sometimes still frozen over when they arrived.

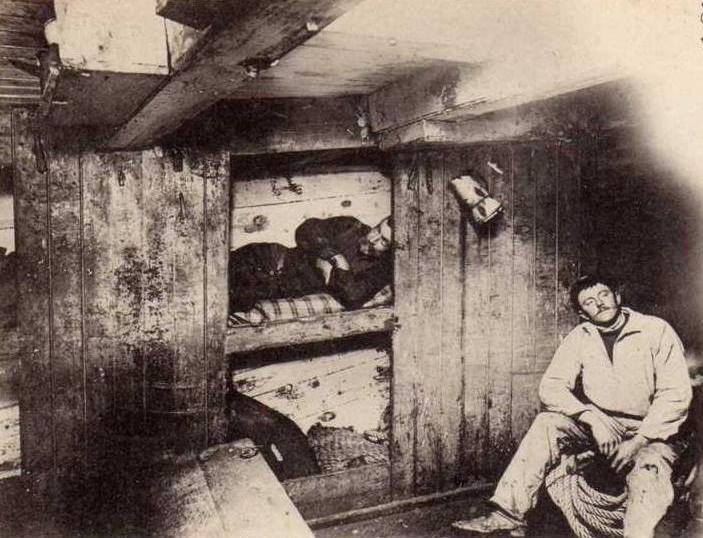

On the benches and on Iceland, life on board was characterized by promiscuity and lack of hygiene. Most of the holds were reserved for salt and cod, and while the captain had a small cabin, the space available for the crew was very limited and almost entirely unventilated. The only bunks available to sailors were one-meter-high bunks stacked one on top of the other, lined with straw matting (which quickly became damp and then rotten) and known as “cabins”. And sometimes there was only one bunk for two men. More often than not, the absence of latrines meant that we had to climb onto the deck to relieve ourselves, and there was no fresh water for washing. The exhausting work in cold, windy, snowy conditions, with days that could last up to 20 hours when the fish were plentiful, drove the sailors to lie down in their cabins, sometimes without even undressing.

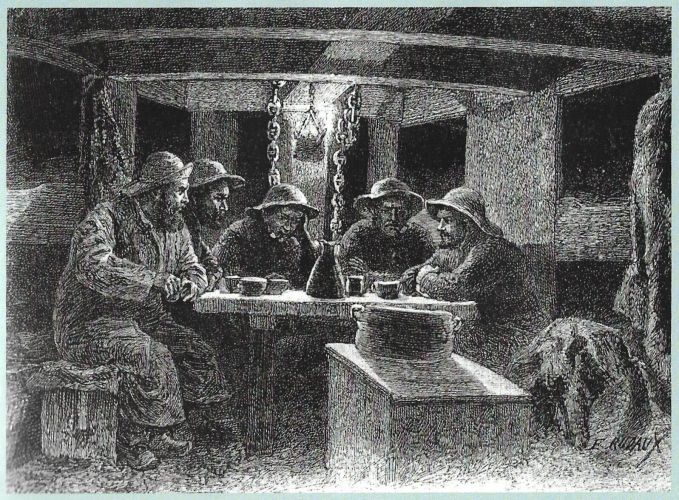

Edmond Rudaux – illustration pour “Pêcheurs d’Islande”.

Food was very mediocre, consisting mainly of sea cookies, cod-head stew, bacon soup, a few fresh vegetables at the beginning of the campaign, potatoes and pulses. Water stagnated quickly, so sailors drank cider cut with water or wine. A daily ration of eau de vie (boujaron) was also provided.

On board, the captain acted as physician and surgeon. All he had at his disposal was an on-board pharmacy, checked before boarding.

Faced with these deplorable sanitary conditions, the Société des Œuvres de Mer, founded in 1894 to “provide material and moral assistance to French sailors and their families”, equipped a number of hospital ships to cruise the banks of Newfoundland and the coasts of Iceland. The Saint-Yves, on which Father Yvon, chaplain to the Terre-Neuvas, sailed and from which you can view film extracts, is one of them. From 1911 onwards, French naval vessels carried out the same mission.

A modest hospital had been operating in Saint-Pierre since the late 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, three small French hospitals, staffed by Breton nurses, were established in Iceland, with a total of around 100 beds.

The most frequent illnesses were typhoid, lung ailments, scurvy, joint ailments… There were also numerous fractures, contusions and abscesses resulting from hook wounds on the fingers… All this pain didn’t stop the men, as their wages depended on their fishing. On board, alcohol was the universal remedy for pain. Alcoholism was a scourge.

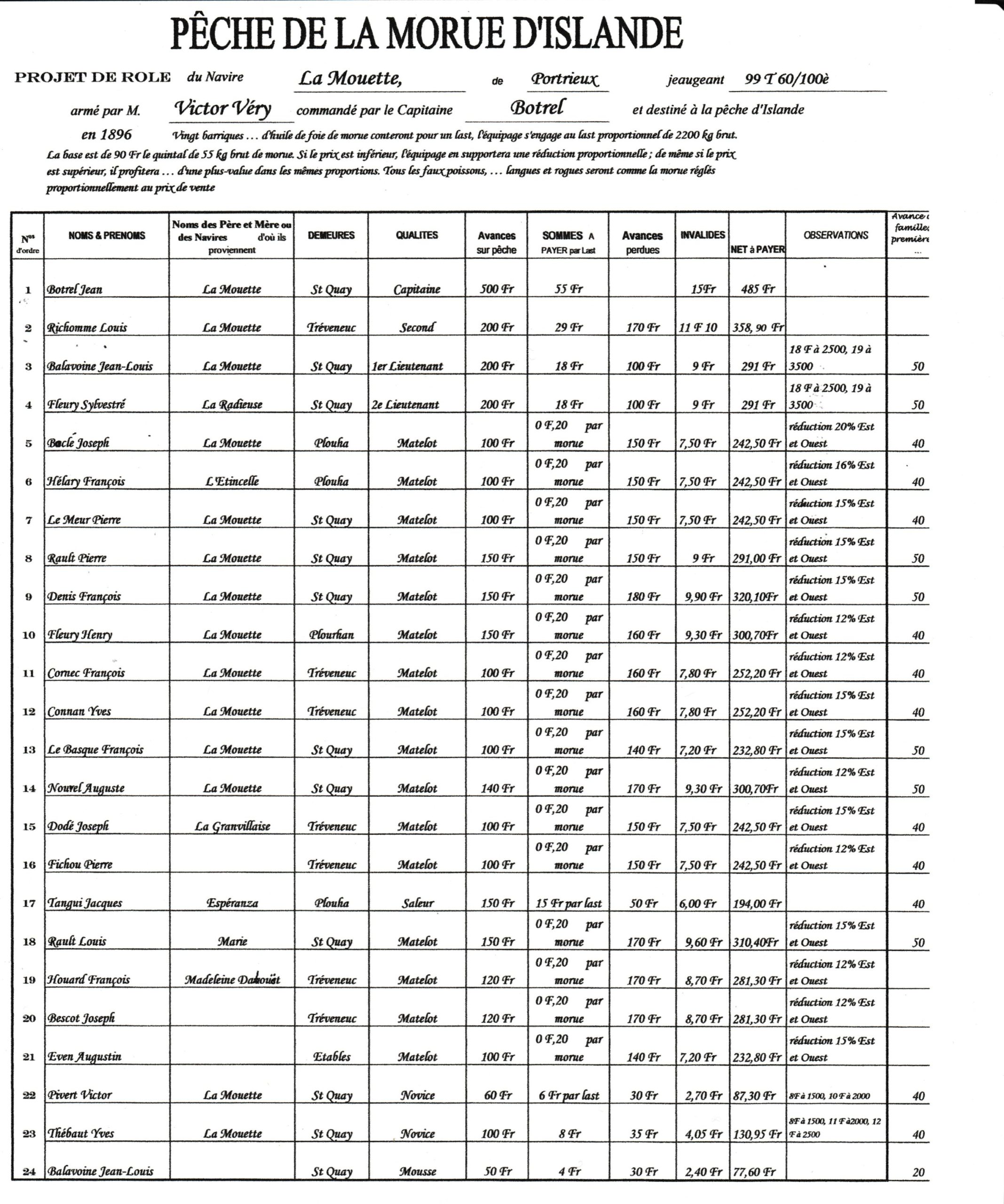

Fishermen’s wages

Sailors were remunerated according to a complex system that took into account the quantity of cod caught by each individual. In simpler terms, the value of a cod was calculated by dividing the net income from fishing (sale of cod and oil minus purchases of boëtte and other expenses) by the number of cod caught.

The exact number of cod caught per man was recorded in a booklet, and they were paid accordingly according to a pre-determined percentage. For dory fishermen, the dory skipper and the bowman did not receive the same percentage. For those who didn’t fish, the salter, the mousses and the novices, the percentage of the total catch was also fixed in advance. The captain’s share was discussed with the shipowner.

The advance received before departure was then deducted from this sum, to enable the sailors to equip themselves (personal effects, oiled work clothes, clog boots, straw mattress, tobacco and small provisions) and their families to wait for their return. This advance varied according to the fisherman’s reputation. A good, experienced fisherman naturally received a more comfortable advance than a beginner.

These wages, better than those of day laborers, supported the families. Alone for long months at a time, sailors’ wives could be washerwomen, hat ironers, seamstresses… and very often supported a small farm, a vegetable garden and a small herd of cattle. On their return, during the few winter months, sailors could fish inshore, work in the fields, help with housekeeping or any other activity for which they were needed. Until 1908, the Saint-Quay-Portrieux lime kiln temporarily employed a large number of them.

Human losses

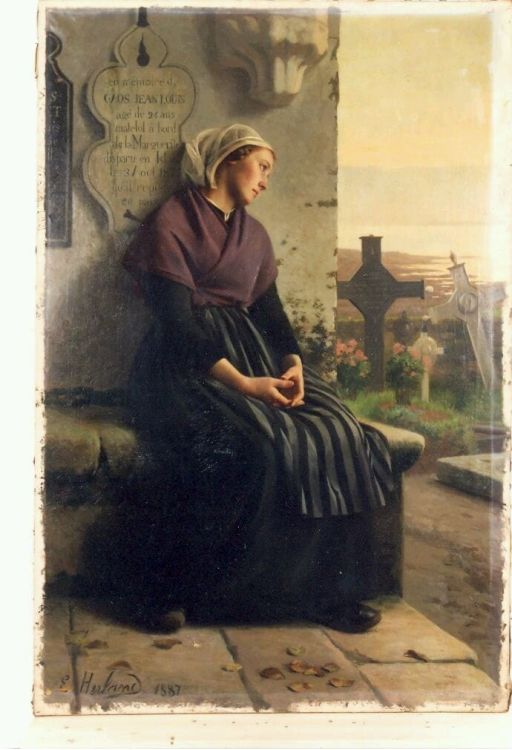

Gaud Mevel – Emma Herland – 1887

Without overall statistics, it’s hard to keep track of the loss of human life in the deep-sea fishing industry. But every year, many sailors didn’t return to port in the autumn.

Shipwrecks, accidents, the disappearance of dories in the fog on the banks, illness – mortality was high. For the 1903 campaign on the banks of Newfoundland, the bulletin of the Société des Œuvres de Mer reported 13 shipwrecks (but only one death), 87 deaths from accidents or loss in the fog, and 102 deaths from illness. In all, 205 deaths, a rate of 28 deaths per 1,000 sailors. An enormous number. Statistics for Iceland put the average mortality rate, all causes combined, at around 12 per 1,000. In the 83 years of fishing in Iceland from the port of Paimpol, some 2,000 people lost their lives, 120 schooners were shipwrecked, 70 of which were lost.

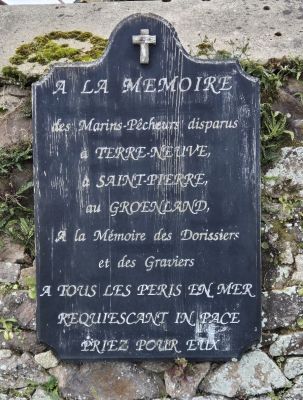

Many of Brittany’s chapels and cemeteries have commemorative plaques to keep alive the memory of those who lost their lives.

Since 1823, a mutual insurance company had been set up in the Bay of Saint-Brieuc to cover the risks of Newfoundland vessels. But no provision was made for loss of life, which was seen as an inevitability against which nothing could be done.

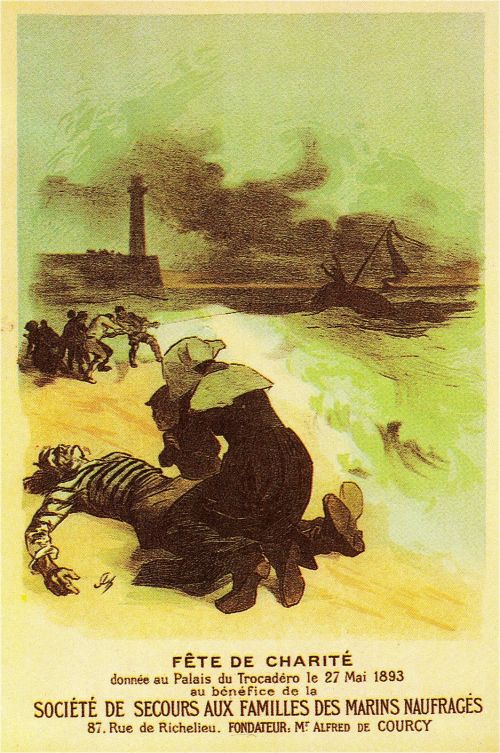

The families of missing sailors, with little or no means of support, depended on public solidarity. Widows received a meagre pension linked to their deceased’s status as a seafarer, and the proceeds from collections and charity events were very little. Founded in 1879, the “Société de Secours aux Familles des Marins Français Naufragés” began to raise funds to provide emergency aid to stricken families and contribute to orphans’ school fees. Nevertheless, the situation of sailors’ widows and the many orphans was very precarious, if not tragic.

Even after the end of the great fishing season, the Société des Œuvres de Mer and the Société de Secours aux Familles des Marins Français Naufragés continued their activities. They merged in 2018 to form the Société de Secours et des Œuvres de Mer.

Why accept such a life?

Convicts of the sea, galley slaves of the mists – there’s no shortage of adjectives to describe the life of the sailors in the deep-sea fishing industry. And yet, year after year, they would set sail again. Economic necessity, no doubt, as sailors were better paid than day laborers, and poverty was rife both in the countryside and on the coast. Or out of habit and family tradition. And sometimes, out of personal choice of what they called “the great profession”.