Places, fishing techniques and boats

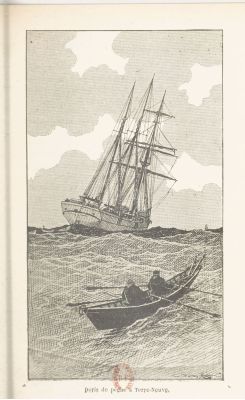

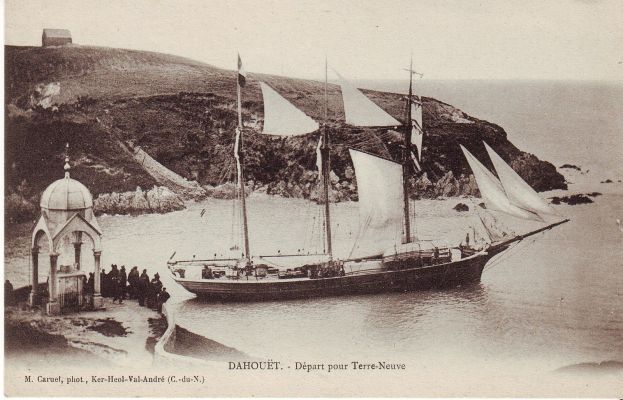

Départ pour les Bancs

We’re all familiar with the cod we eat fresh. But once salted and/or dried, this fish takes on the name “cod”… It’s called “dry cod” if salted and dried, and “green cod” if simply salted.

This cold-water fish ranges in size from 50cm to 140cm, with the largest weighing over 20kg. Until the middle of the 20th century, it was abundant in the waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, around Newfoundland, Greenland and Iceland.

The high quality of this fish, the possibility of preserving it salted and dried and transporting it to distant regions, and the oil that could be extracted from its liver made it an extremely attractive resource that attracted European fishermen as early as the 15th century. So they didn’t hesitate to cross the oceans to Newfoundland, the Grand Banks or Iceland, to bring home this precious food.

But this success had a downside. Fished too intensively, the cod population has declined sharply. Since 1992, cod fishing has been banned east of Canada, and Icelandic waters are now closed.

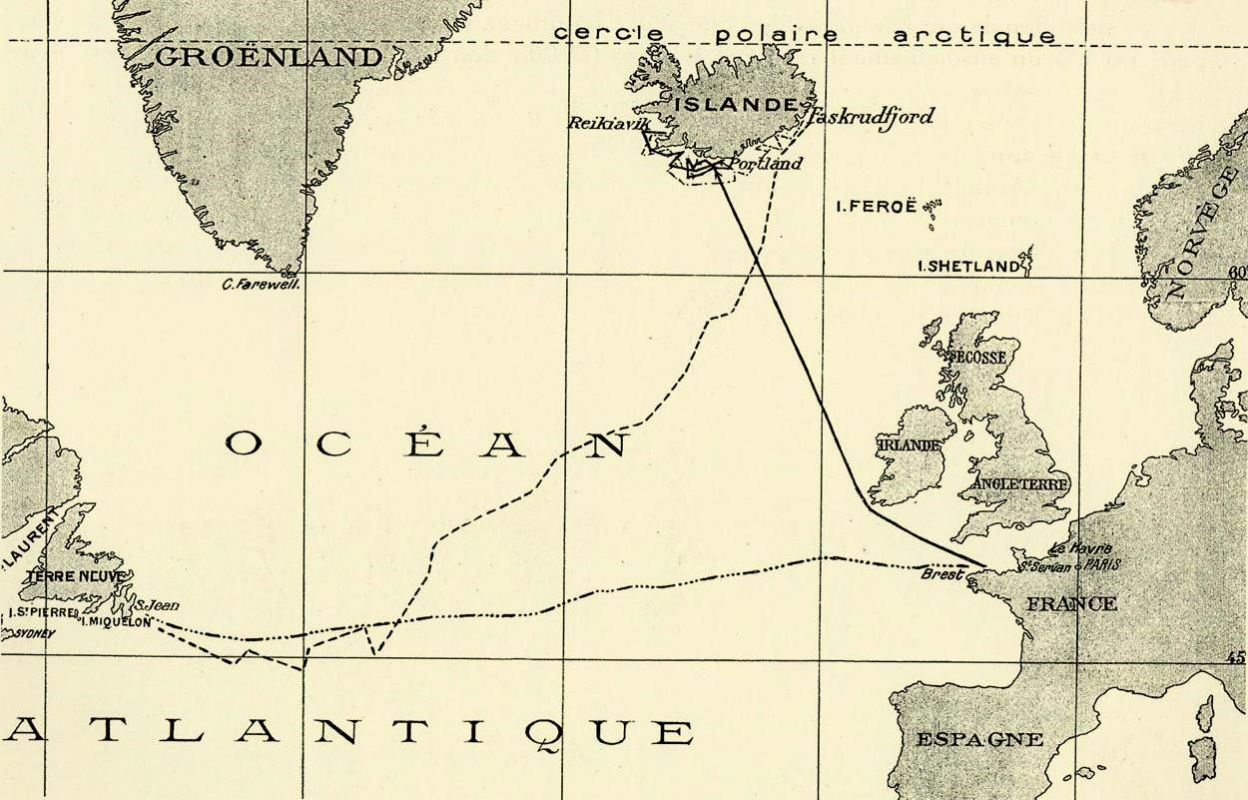

For three centuries, long-distance cod fishing was the main activity of Breton fishermen in general, and of those from the Bay of Saint-Brieuc in particular. The fishing season took place between late spring and autumn, as cold and sea conditions were too extreme in winter. Around March, ships and crews set off for 6 or 7-month campaigns. Three destinations followed one another, each with its own history and techniques…

Terre-Neuve et Islande, deux destinations bien différentes.

Newfoundland

Between the 15th and mid-19th centuries, the main destination for cod fishermen on our coasts was Newfoundland.

Carte réduite de l’île de Terre-Neuve – 1784 – Service Hydrographique de la Marine

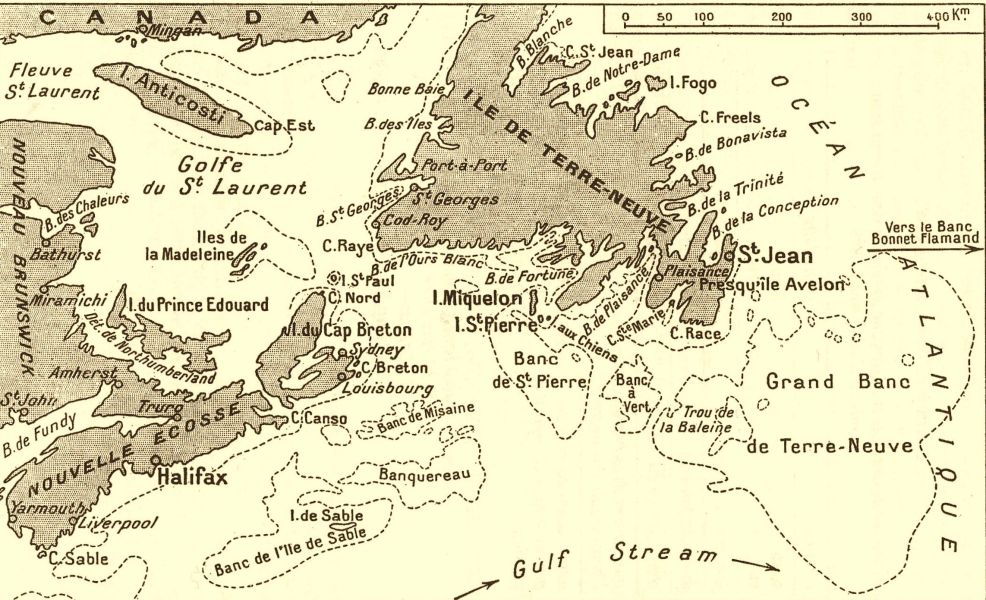

Conflicts with England over possession of the island led to a division of the fishing territory in 1713. Until the mid-19th century, fishermen (mainly from Brittany and the Basque Country, with a strong contingent from the Bay of Saint-Brieuc) had exclusive fishing zones and the right to build and use onshore facilities. This practice was known as “sedentary fishing”.

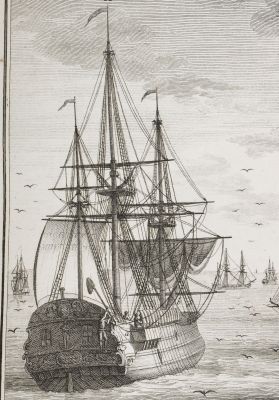

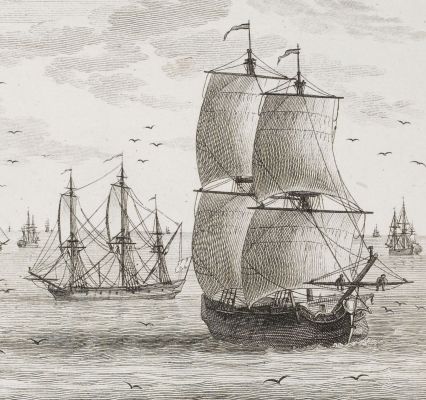

The two- and three-masted ships left our shores in March, with crews of between 40 and 60 men. To reach the coast of Newfoundland, until the 18th century, all types of vessels large enough to carry large fishing boats and a large crew were used. In the 18th century and beyond, brigs (2-masts) or 3-masts like those depicted by Eugène Boudin were used.

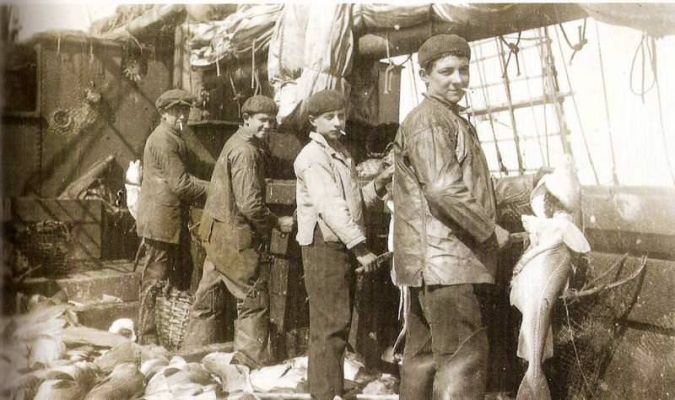

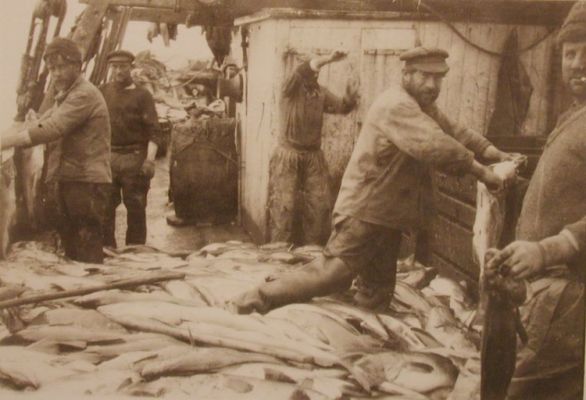

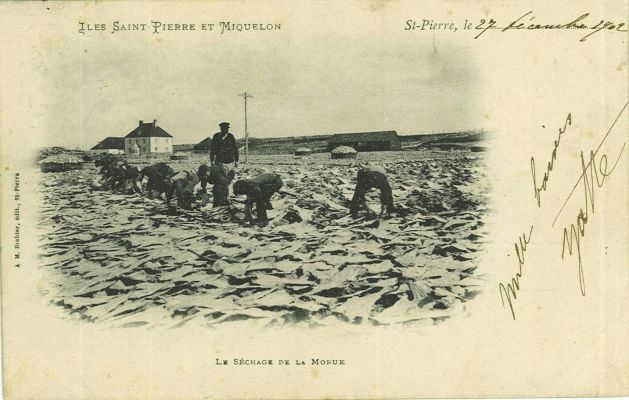

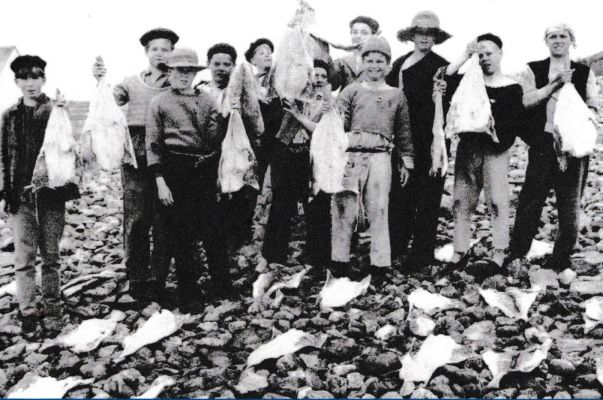

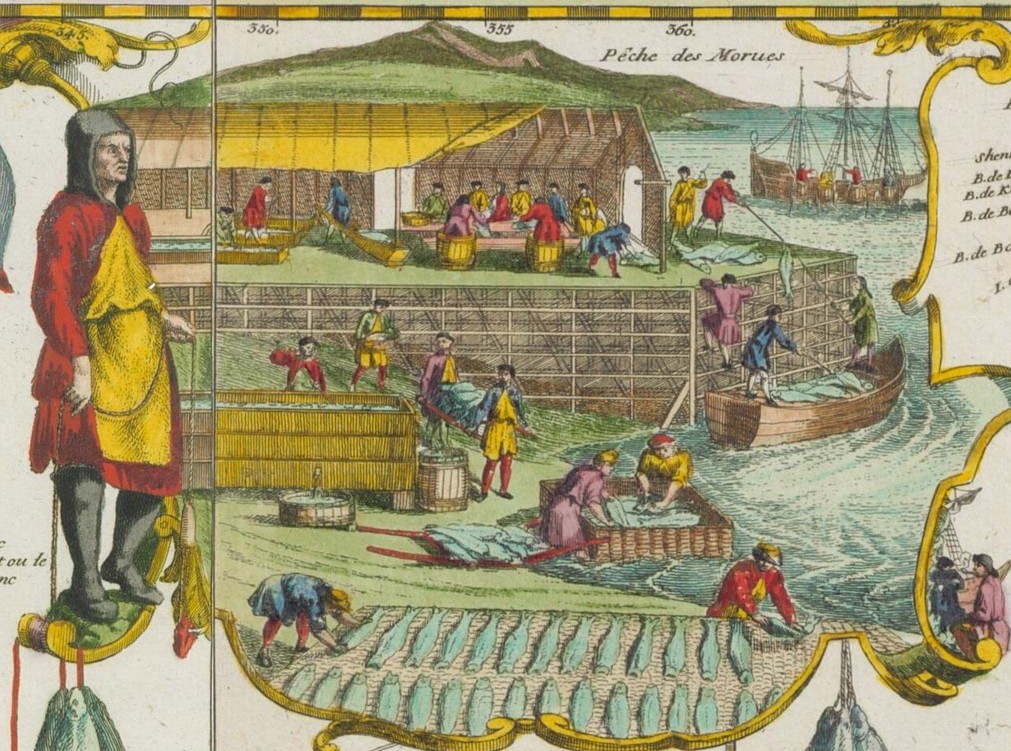

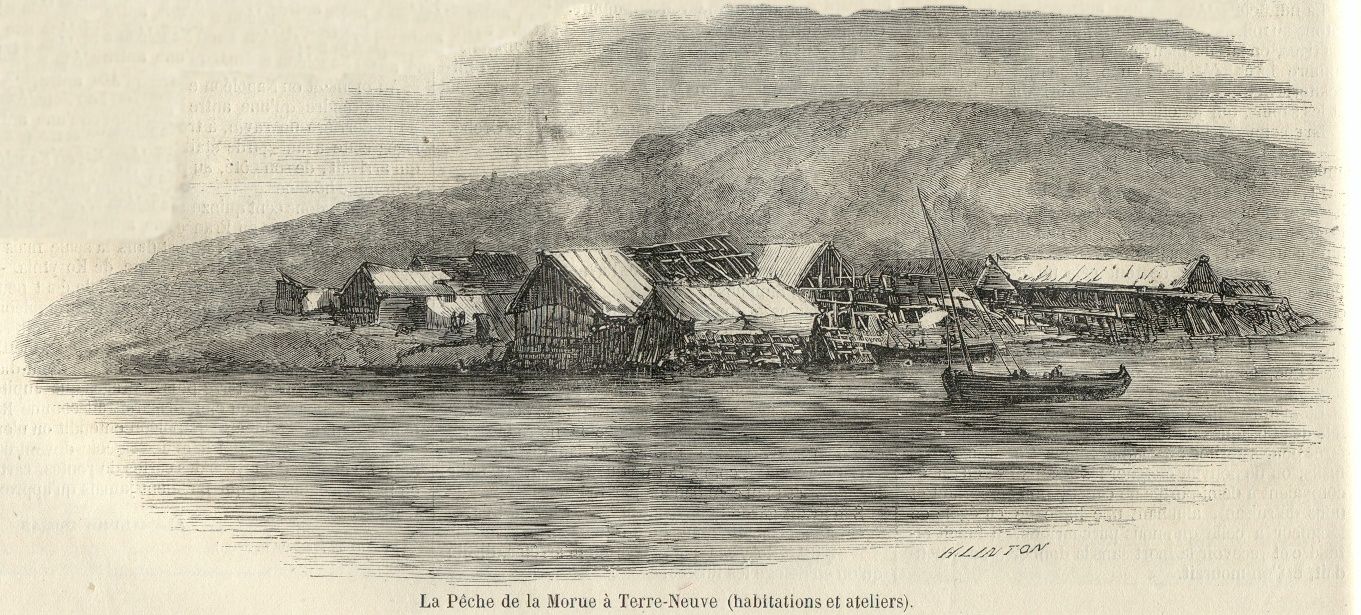

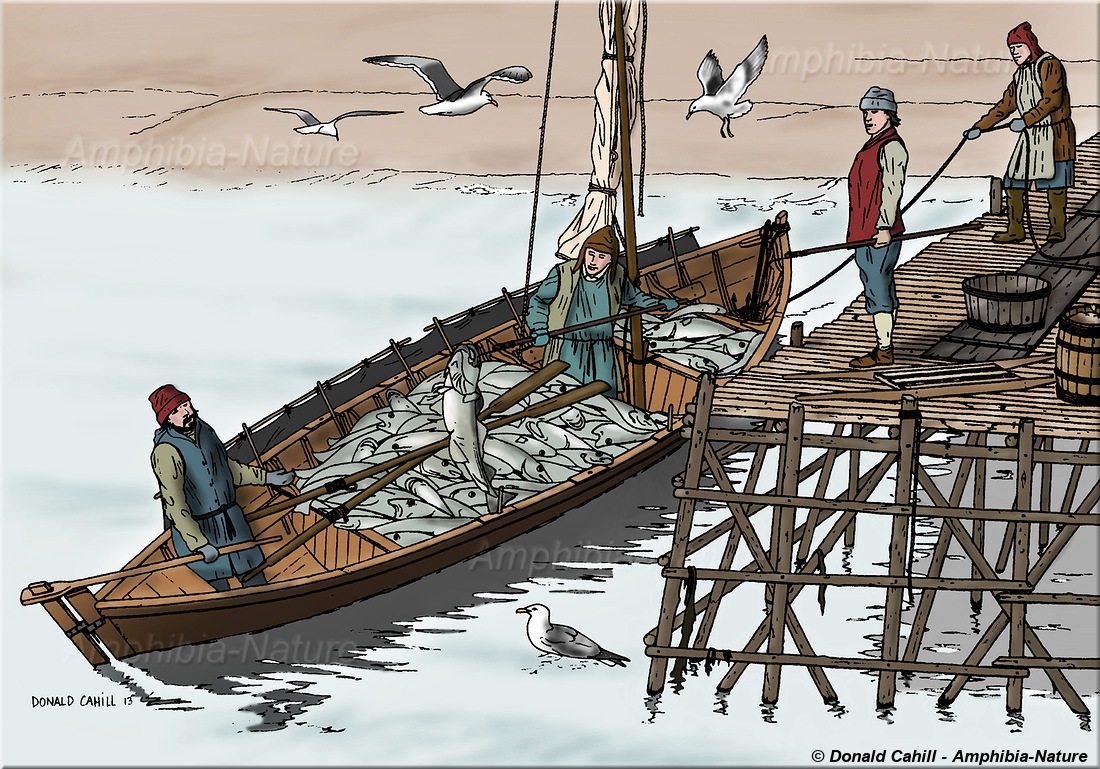

After a 3- to 4-week crossing, depending on sea and wind conditions, they dropped anchor in Newfoundland harbors. Arrival could be difficult if the island was still covered in pack ice. The boats, manned by 6 to 8 men, set out from the coast and returned to shore each evening. The fish was then prepared – the cod was said to be “dressed” -: opened, gutted, headed and stripped of its central ridge, salted and finally laid out on the “graves”, flat stone beaches ideal for drying the fish. Young children and teenagers from the Goëlo hinterland were entrusted with this thankless task, carried out in difficult conditions. They were known as “graviers” and are depicted in the drawing at the top left of the panel.

The return trip generally took place towards the end of September or in October. This “dry cod” was brought back to the home port to be sold. But some ships didn’t return directly to their home port, and sailed with reduced crews to Marseille or other Mediterranean ports where cod prices were more favorable.

After filling their holds with a variety of goods (oil, wine, soap, etc.), they set off on their return journey, stocking up on salt and brandy for the next campaign. This return journey was made against the wind, the passage of Gibraltar could be problematic, and the ascent of the Bay of Biscay turned into a real ordeal for these heavy ships, which had to sail against the wind.

Some even had to ration food if the voyage was prolonged.

Le Portrieux sailed to Newfoundland from the 16th century until 1886. In the Bay of St Brieuc from 1850 onwards, the restriction of fishing rights in Newfoundland and the decline in the resource led shipowners to prefer fishing on the banks.

Carte de Terre-Neuve – Nicolas de Fer – 1713 (détail)

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland

Why the name : “the banks”? These are a series of underwater plateaus southeast of Newfoundland, at the confluence of the Gulf Stream and the Labrador Current. Their depth, for the most part between 50 and 100 meters, and the nutrients brought up by the currents, make them an ideal zone for all kinds of animal life, and therefore for fishing.

We know that fishing on the banks of Newfoundland has been practiced by ships from the Bay of St Brieuc since the 16th century, but to a lesser extent than sedentary fishing. It reached its peak in the second half of the 19th century.

Fishing on the banks was called “wandering fishing”.

Vessels were the same as on the Newfoundland coast: brigs or 3-masts with crews of between 30 and 40 men.

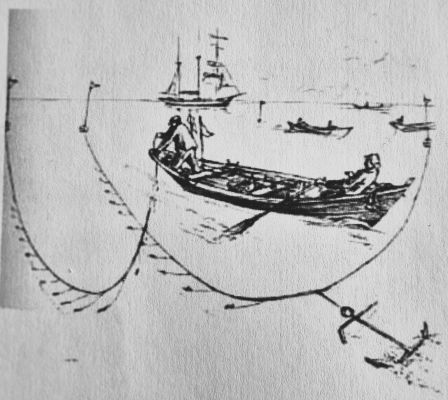

At first, fishing was carried out from the edge of the boat. The ship, under reduced sail, drifted along, and each fisherman (seated in 1/2 barrels behind the rail) let out lines.

From the end of the 18th century, the ship was anchored and large rowboats with a dozen men were launched to set bottom lines, which were hauled out twice a day. Then, in the second half of the 19th century, came the famous “dories” that could be transported stacked on the deck of the ship, generally 10 to 12 per boat. With two men on board, the dory skipper and the dory bowman, lines 1,500 to 2,000 meters long fitted with nearly 2,000 baited hooks were set and hauled out twice a day. These light boats are still remembered today, and the technique continued until the arrival of motorized trawlers in the mid-20th century. Dory fishing was highly productive. But it was also very dangerous, as sea conditions were often violent on the shoals, and fog was frequent. These fragile boats could get lost. The loss of life on the shoals was considerable.

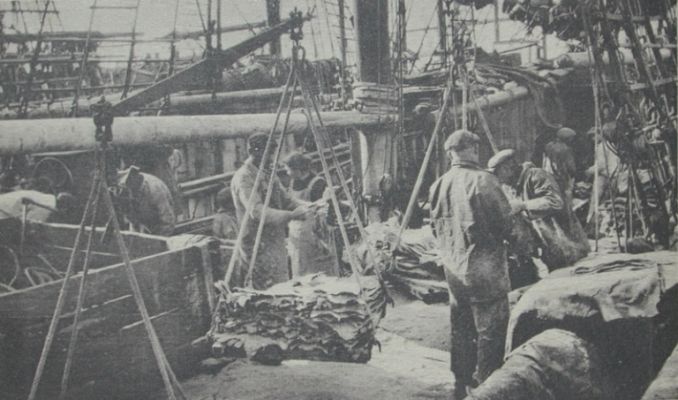

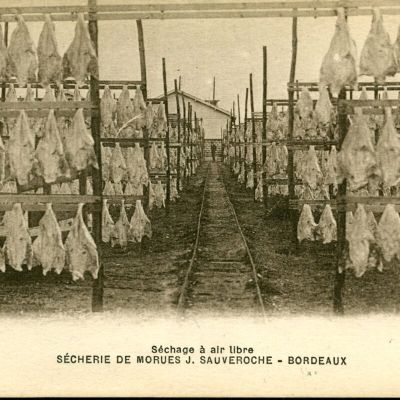

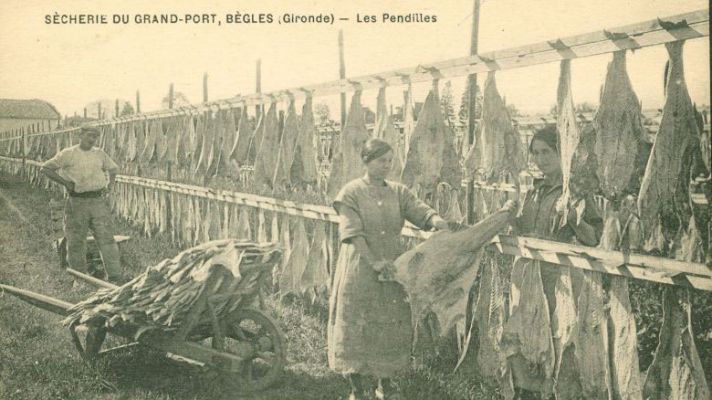

Once back on board, the fish was prepared (“dressed”) on deck and salted in the ship’s hold. It remained there until returning to its home port, unless a stopover in Saint-Pierre et Miquelon enabled the first catch to be unloaded and the salt replenished. Cod preserved in this way is called “green cod”, and has a shorter shelf life than dry cod. Once unloaded, the cod must be washed and brushed to remove the salt, then put out to dry in the open air.

In the second half of the 19th century, only the banks were fished. The archipelago of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, which remained French, became an obligatory stopover for supplies, medical care, mail… but also to stock up on salt and boëtte (bait) before setting out again for the second fishery. The landed cod could be dried on the gravel of Saint-Pierre and transformed into dry cod, a job entrusted to young boys from the Breton hinterland, the “graviers”, who performed it in conditions akin to slavery. Ships could also bring their cargo directly back to France to be dried. At the beginning of the 20th century, green cod was processed in mechanical dryers installed in major landing ports.

Le Portrieux, with its close ties to the Newfoundland coast, did little bank fishing. In the Bay of Saint-Brieuc, it continued until the First World War, but with less intensity than on the coast of Newfoundland.

Island

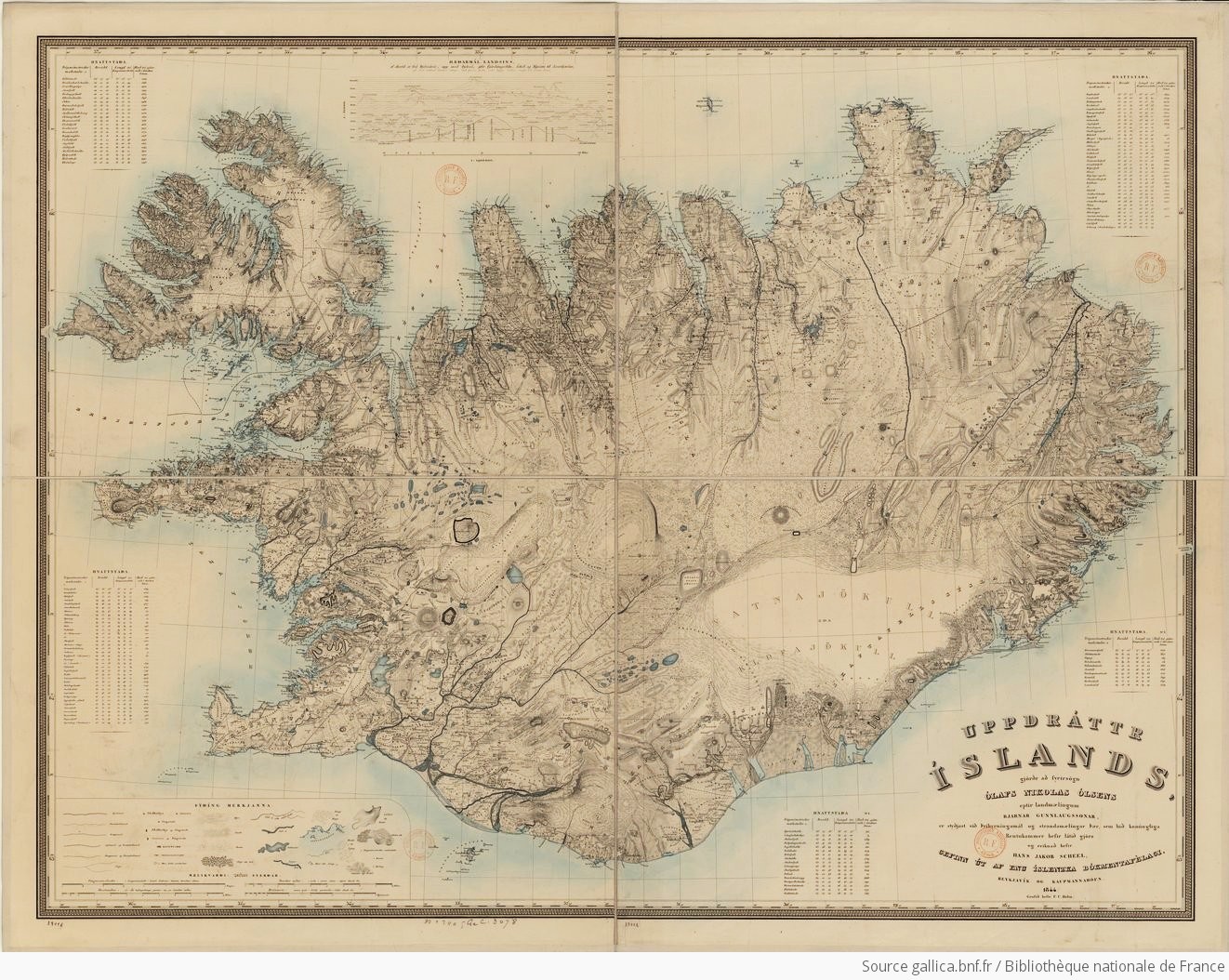

Carte d’Islande en 1844 – Olsens Olafs

On this coast of jagged shores and deep fjords, storms and hurricanes were frequent, and the sea was violent. But fish were plentiful, whereas they were scarce around Newfoundland.

Icelandic territorial waters, forbidden by a Danish monopoly, were opened up in 1766, but without allowing foreign ships into the ports. In 1854, it was finally possible to go ashore. From then on, to make the most of these fish-filled waters, shipowners turned en masse to fishing “in Iceland” – since there was practically no landing, you weren’t “in Iceland”.

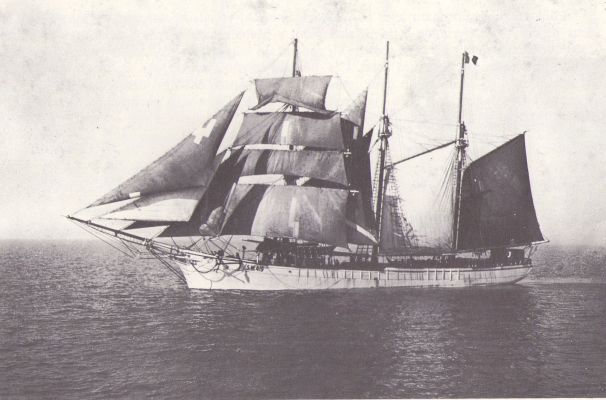

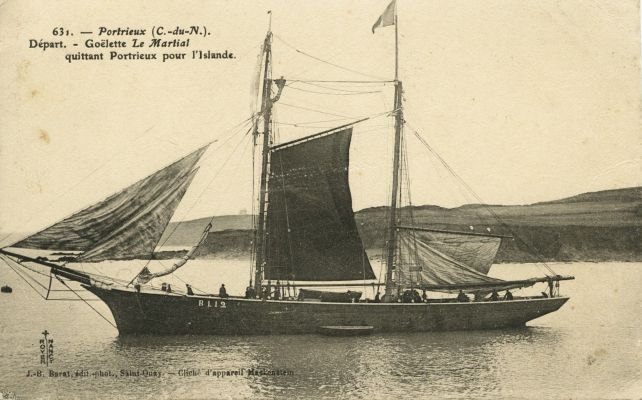

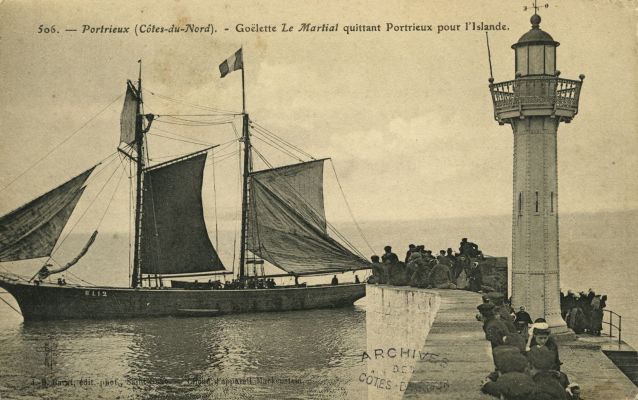

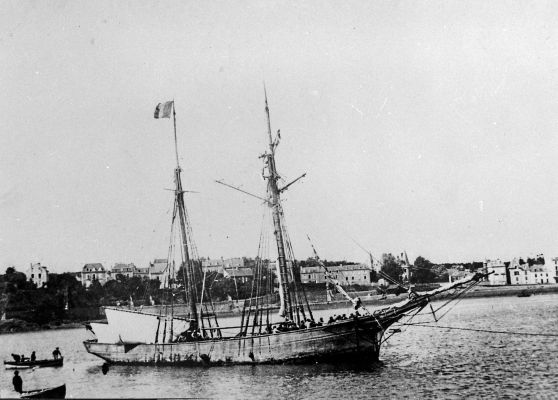

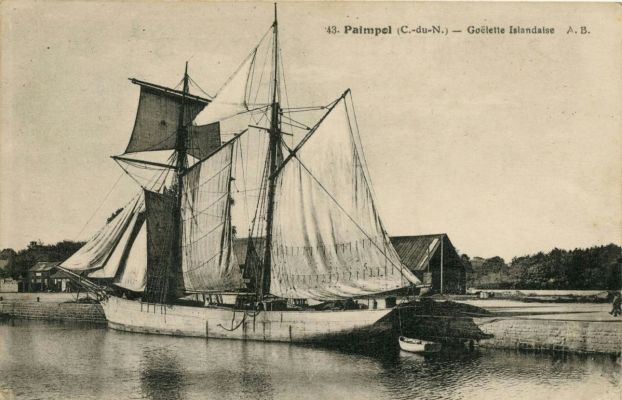

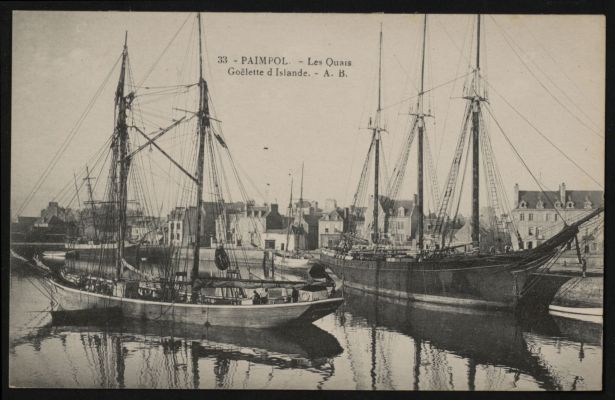

The vessel best suited to the Icelandic destination was the paimpolaise schooner, slender, light and much more maneuverable than the large 3-masted vessels of Newfoundland and the banks. Fishing from the shore, there was no need to take on board a “dory”, as the crew consisted of around thirty men, sometimes fewer.

After about ten days’ sailing to reach the fishing grounds, the campaign began in early March and was divided into two periods. From March to May on the south coast, the second in summer to the north and east of the island, over deeper waters and further from the shore. The return trip took place in September.

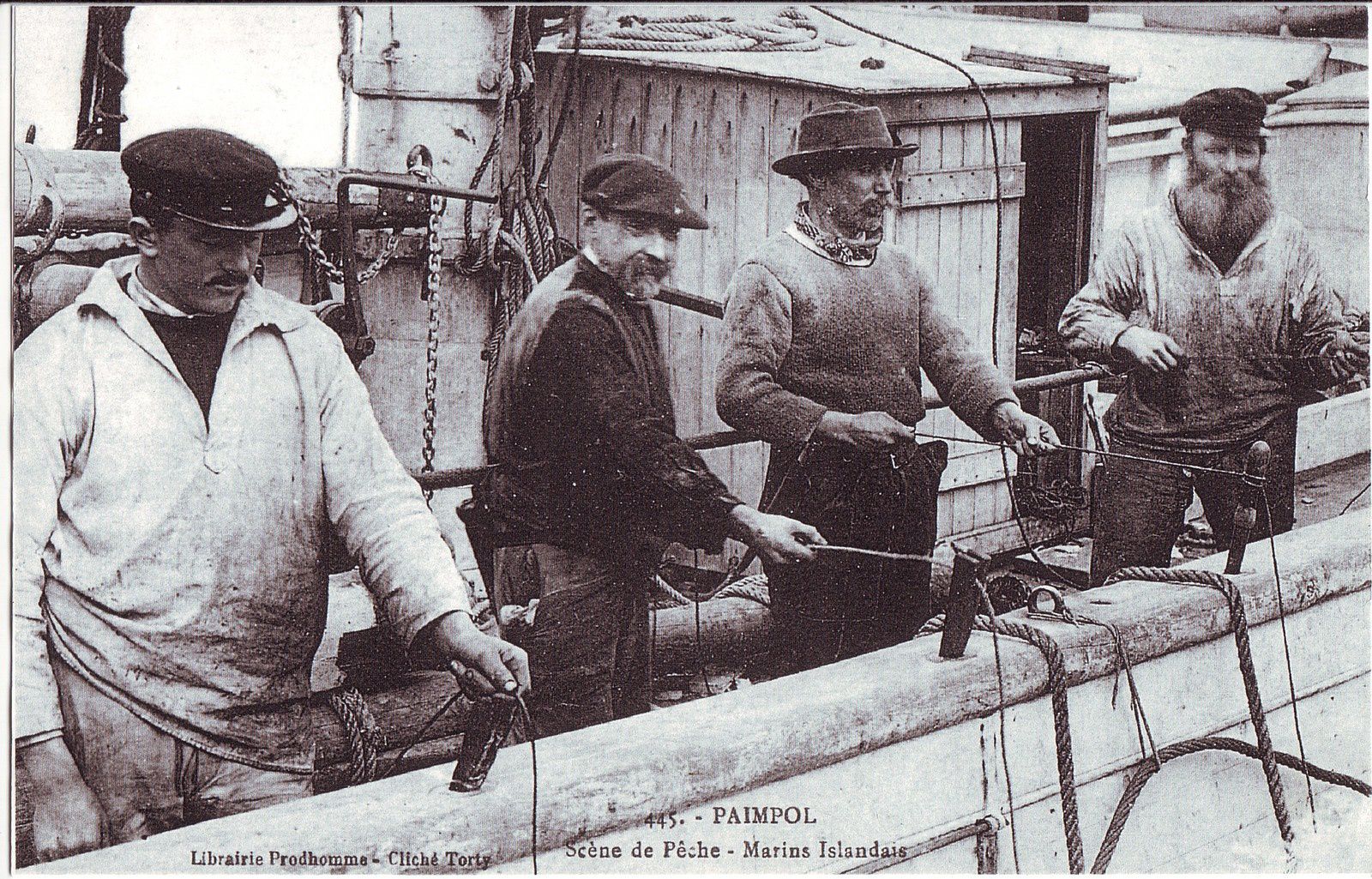

Fishing on Iceland was done “à la traîne”. The schooner sailed under reduced sail. Each fisherman held a line from the shore. Two to three hundred meters long, heavily weighted with lead and fitted with numerous baited hooks, this line was extremely difficult to reel in.

As on the shoals, once on board the fish were “dressed” on deck, then salted and stored in the ship’s hold until the end of May, the end of the first fishing season.

For another month, the ship could lay up in a fjord. Each port had its own routine: for Le Portrieux and Binic, it was Patrixfjord. Rest, washing and grooming for the men, who enjoyed the Icelandic hot springs, boat maintenance, provisioning… The load of fish was taken by a “hunter” ship chartered by the shipowner to be sold as quickly as possible. Then it was time for the second campaign, before the return trip in September.

Paimpol, the emblematic port of the “Icelanders”, was immortalized by Pierre Loti. The ports of the Bay of Saint Brieuc, Binic, Le Portrieux, Le Légué and Dahouet, also set sail for Iceland, while fishing on the banks of Newfoundland. In Portrieux, the year of the biggest departures for Iceland was 1870, with 18 vessels outfitted (43 for the whole of the Bay of Saint-Brieuc and 48 for Paimpol). Around 1895, Paimpol had more than 80 ships…

This fishery ceased shortly after the First World War, as steam-powered cod boats replaced schooners and Iceland limited access to its territorial waters.